No, I’m not sure what a moose has to do with Montreal. Bookmarks can be random like that.

Book: Montreal Stories by Clarke Blaise

No, I’m not sure what a moose has to do with Montreal. Bookmarks can be random like that.

Book: Montreal Stories by Clarke Blaise

Fools on the Hill

By Dana Milbank

Page I bailed on: 38

Verdict: Washington Post reporter Dana Milbank’s previous book The Destructionists: The Twenty-Five-Year Crack-Up of the Republican Party did a decent job giving an account of the historical process that culminated in the triumph of the Trump MAGA movement. This book is more like a reporter’s notebook though, and is mainly just a collection of pieces on the clown show that Congress turned into in the 2020s.

But if you follow politics you probably already know more than enough already about figures like Marjorie Taylor Greene, George Santos, Lauren Boebert, Matt Gaetz, and all the other “hooligans, saboteurs, conspiracy theorists, and dunces” who attracted so much media attention. And it didn’t take long before I got tired of the litany of outrageous pronouncements made by these whackos on social media, and the scandalous behaviour of this lunatic fringe. One question still in need of answering is how much of this is just performance and how much is the expression of sincerely held beliefs (read: psychosis). Though I suspect that at this point the performance may have created its own alternative reality, making the question moot.

So this is another DNF that isn’t a bad book but that I just didn’t feel any need to stick with for 350 pages, especially as I skimmed ahead and didn’t see where Milbank was coming to any new or profound conclusions about what was going on. “This is no way to run a country and certainly no way for a democracy to function,” he says at one point when talking about the outsized influence the crazies have. “But this is our current reality.”

Except the book came out at the beginning of 2024 and the “current reality” was about to get a lot worse.

Fresh meat. Meaning a new writer (Fred Van Lente) and artist (Kev Walker). And I was looking forward to a change in the storyline, since (as I’ve previously noted) I wasn’t that thrilled by Robert Kirkman’s first two volumes. I found Walker’s art nearly indistinguishable from that of Sean Phillips so didn’t register any change on that account.

Fresh meat. Meaning a new writer (Fred Van Lente) and artist (Kev Walker). And I was looking forward to a change in the storyline, since (as I’ve previously noted) I wasn’t that thrilled by Robert Kirkman’s first two volumes. I found Walker’s art nearly indistinguishable from that of Sean Phillips so didn’t register any change on that account.

And . . . Van Lente really came through. The story here is tight, not at all like Kirkman’s sprawling and confused cosmic zombie epic. If you want you could see some continuity with the previous books, but basically this is a standalone. There’s a zombie universe in play, meaning one that has been taken over by zombies. Unfortunately, since the zombies have finished eating everything they’re now looking for new worlds to colonize/devour, or whole new universes where they can spread what they’ve taken to calling the “Hunger Gospel.” Which would be the zombie virus. Same thing.

Zombie Kingpin is top dog in this zombie dimension, but he has lots of flunkies. Among them is zombie Doctor Strange, who can cast a portal to other locations in the multiverse. This, in turn, lets zombie Morbius and zombie Deadpool infiltrate a secret inter-dimensional facility that exists in our world.

To what end? Well, the zombies have a wicked plan cooked up whereby they will pretend to inoculate all of our superheroes against the zombie virus while really infecting them with the same, which will then make us easier to take over. Man, that’s what I call dirty pool. Not to mention a storyline that feeds into every anti-vaxxer’s favourite conspiracy theory.

Trying to stop them are Machine Man and Jocasta, who have to visit the zombie universe and then make it back. To be honest, if Jocasta did anything on this mission I’m not sure what it was. But Machine Man really kicks ass. He’s a one-man zombie Armageddon. But will that be enough?

As things got started I was wondering if I was going to be able to get into it. Once again, things are very dark. Dark in a way that deadens the wisecracking and attempts at humour. I get the gore, and the fact that zombies do eat people. But Van Lente continues with Kirkman’s thing for heroes being tied up and then cannibalized, which reminds me of the people kept in the basement of the house in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Here they even have a clone farm in the zombie universe to keep the hungry dead fed on vat-grown meat. And even heroes who aren’t as good to eat are also kept vaguely alive, if you can call Morbius or Vision alive, just so that they can be tortured. To be honest, I wasn’t sure why else Morbius and Vision were being kept around, except to add to the whole theatre-of-cruelty effect that’s going on.

If you can handle all that, the story itself is pretty compelling and I read the whole book in a rush. It really helps that things are more streamlined than in Kirkman’s comics, as the action is a lot easier to follow. Given how fast things move, this was a big plus. Throw in some fun stuff like zombie Captain Mexica (a Mexican Captain America preserved from an alternate timeline where the Aztec empire never fell), a bonus section of the usual parody covers (not just of famous comics but of movie posters too), and a relatively happy ending, and I ended up having a good time. In my opinion it was the best Marvel Zombies book yet, and had me finally looking forward to what’s next on the menu.

The crime:

In 1920s Chicago a lawyer named Leo Koretz who had a taste for the finer things in life – married women, nice clothes, big houses, expensive dinners – went into the financial scam business. What this involved was selling shares in a non-existent company called the Bayano River Syndicate that he said had discovered oil in a remote part of Panama. The scam operated as a Ponzi scheme, paying rich dividends out of the money pumped into the stock by new investors. Just before being exposed, Koretz fled Chicago, abandoning his wife and family, and opened a hunting lodge in Nova Scotia under a new identity. He was eventually discovered and returned to the U.S., where he pled guilty to charges of fraud and was sent to prison. He died shortly thereafter, some say from suicide after eating a box of chocolates that put him into a diabetic coma.

The psychology of the Ponzi scheme has always puzzled me. Not the psychology of those who invest in them; they’re only in it to make a quick buck. Are they suckers? Some of them. But ignorance, if not bliss, is still advisable in such situations, and Koretz didn’t appreciate doubters. So either way, that part is easy to understand.

What I have trouble understanding is what the person operating the scheme is thinking.

As anyone who considers the matter even for a moment knows, a Ponzi scheme always carries within it the seeds of its own destruction. The music has to stop. Scams where new money is paid out as supposed returns on investment are “doomed to collapse” because of an inherent flaw: “There is never enough money for all . . . and the inflow of new money must ultimately dry up.”

Knowing all that, what is the end game? Do the fraudsters who run such schemes just find themselves stuck on a treadmill they can’t get off? Do they think there’s some way they’re going to be able to defer the inevitable crash, if not indefinitely at least until something else comes up? I don’t know.

Koretz seems to have been a particularly complicated case. After his arrest he would claim that he almost came to believe in the oil fields himself:

“I talked Bayano, and planned Bayano, and dreamed Bayano, so that I actually believed the stuff. The idea grew and grew. Every day I spoke more of it until, finally, I was confident. It almost seemed that I had those thousands of acres and that oil down there in Panama.”

Ah, yes. It “almost seemed.” I think in the case of Charles Ponzi this might be close to the truth. But Koretz wasn’t as high on his own supply of bunko. “I knew the bubble would burst,” he also later confessed. And he did have a plan for getting away with it. Not that well thought out a plan, to be sure, but still a plan.

It began by sending a team of his most prominent investors on a trip to Panama to inspect the oil fields for themselves. He told them they would be surprised by what they found, and sent a final cable to them saying only BON VOYAGE, signed by THE BOSS. (In turn, the investors’ cable home would summarize their findings: “NO OIL, NO WELLS, NO PIPELINES, NO ORGANIZATION.”) I had trouble figuring this trip out, and the cruel mockery in that “BON VOYAGE.” The investors felt that being sent to Panama “had been a ploy to get them out of the way while Leo planned his escape,” but I think he must have already made his plans to get away by then and I don’t see where it helped him much to have them out of the country. When later asked about why he’d arranged this wild goose chase when he knew what the investors would find, he replied that he “was disgusted at myself and disgusted at the people who had wealth and demanded something for nothing. . . . And I was indifferent as to how the matter ended.”

There may be some truth in this. I don’t think he was indifferent to his likely fate, as he tried hard to avoid it. I’m also not sure how disgusted he was with himself. But his disgust at the people he conned rings true, in part because he must have seen a bit of himself in their wanting something for nothing.

This is a really good book, but I found it hard to be sympathetic toward Koretz. For example, he restricted his list of investors to friends and family. These were the people he took advantage of? He did give family members large gifts of cash just before he disappeared (money that they, miraculously, returned to the authorities), but targeting those closest to him instead of random strangers reveals a certain degree of heartlessness. It came as no surprise to me that he ditched his wife and children when he pulled a runner, not even bothering to get in touch with them while living a life of pleasure in Nova Scotia.

Women made up a big part of that life of pleasure. And here too one finds it hard to warm to Koretz. Canadian observers referred to his “fickle and insatiable appetite for women,” that saw him “passing from one woman to another like a hummingbird in a flower bed.” He was a good dancer, but aside from that the only source of attraction would have been his ostentatious wealth. That, and what later pick-up artists would describe as “negging”: “I am always indifferent to them,” he’d explain about his way with women, “and sometimes I am downright rude, but it just seems to make them want me more than ever. I don’t know what I do to make them behave so foolishly.” But of course he did know. Jobb notes how it’s “the same reverse psychology he had had used so effectively to sell millions of dollars’ worth of bogus stocks.” A con man is always playing a con.

Did he have any good qualities? Jobb thinks so. “Leo, whose ambition and self-confidence knew no bounds, could have been a top-flight lawyer, a business leader, or perhaps a powerful politician. He chose, instead, to become a master of promoting phony stocks.” Is this true? This is one of the abiding mysteries I find about the criminal mind: why people who could make money honestly choose to instead take up a life of crime, which they work every bit as hard at. This leads me to think that they probably couldn’t be successful with a legitimate job. The Illinois state’s attorney, for one, expressed surprise at the success of Koretz’s con: “people seemed to throw their money at him. . . . Koretz is not what one might call a brilliant man. . . . He is not fascinating or particularly impressive. But people threw their money at him! That’s what astounds me.” Yes, this is judging Koretz after the fact, but I don’t think Koretz was “particularly impressive” in any regard. As so often in such cases, his status and power was a gift bestowed upon him by people who should have known better.

I’ll confess I don’t recall ever having heard of Koretz before reading this book. Jobb argues that this is unfair. We still talk about Koretz’s Chicago contemporaries Leopold and Loeb, and Al Capone. And while another financial scammer operating at the same time, Charles Ponzi, became more famous,

Leo had devised his more elaborate and more brazen schemes more than a decade before Ponzi came along; he was a marathoner who was running long after Ponzi’s hundred-yard-dash ended in a prison cell. Fame and notoriety, however, went to the fraudster who stumbled first and died last. It is fitting, perhaps, that a man who spent much of his life cheating others was cheated out of his rightful place in the history of financial scams.

“In terms of the scale of their frauds, staying power, and sheer audacity, Leo Koretz and Bernie Madoff stand apart in the pantheon of pyramid-building swindlers.” At least grant the man a bad reputation.

If Koretz has been forgotten in the mists of time, the Bayano River remains equally hidden from view, “almost as remote and little known as it was when Leo made it the talk of Chicago.” A lot of Panama is still pretty wild, including the nearby Darién Gap, an area so called because it’s the only break in the longest road on the planet: the Pan-American Highway, running from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska to Ushuaia, Argentina. According to Wikipedia the Gap is considered to be “one of the most inhospitable regions in the world.”

But even though the location of the Syndicate’s oil fields was well off any beaten track, Jobb says that a bit of research in one of Chicago’s public libraries would have turned up the fact that Panama wasn’t a major oil producer. Nor did anyone bother to talk to players in the oil industry – people likely to know about a pipeline spanning the Isthmus of Panama and oil fields producing 150,000 barrels a day. Of course today you could go on the Internet and call up satellite images of the Syndicate’s oil fields to see what was going on for yourself. But while in the 1920s willful blindness was easier to maintain, it still took some effort. This is the bitter truth underlying most cons: They’re rarely victimless crimes.

Noted in passing:

The state prison at Joliet that Koretz was sent to was a grim place, with dark, tiny cells where inmates had to use a bucket instead of a toilet. And apparently they didn’t like con men:

How well he [Koretz] would hold up in prison, and for how long, was an open question. Con men were among the lowest of the low in Joliet’s hierarchy, shunned and almost as detested as sexual offenders. They tended to be older and better educated than the men locked up with them, and had betrayed the only things that mattered inside – loyalty and trust.

This surprised me. I would have thought that being a con man would be seen as having some cachet: using your brains instead of violence to take advantage of people who were just greedy anyway. So I was curious enough about this to check Jobb’s source, which turned out to be Nathan Leopold’s prison memoir Life Plus 99 Years. I guess he’d know.

Takeaways:

Cons today are both easier and harder to pull off than they were a hundred years ago. Easier because scammers can use the Internet and social media to infinitely expand their reach. But harder because the same technology makes it quick and easy to check things out. In a time when so much information is literally at investors’ fingertips there’s no excuse for not taking advantage of the tools you have and doing some basic research into claims that would seem to ask for it.

If you’ve been following along you’ll remember that I’ve taken note of the presence of Deathstroke lurking in the shadows of the previous two Titans books I’ve reviewed (The Return of Wally West and Made in Manhattan). I’d started in on Titans Volume 3 when I found a reference to the team’s battle with Deathstroke in the past tense. Had I missed something?

If you’ve been following along you’ll remember that I’ve taken note of the presence of Deathstroke lurking in the shadows of the previous two Titans books I’ve reviewed (The Return of Wally West and Made in Manhattan). I’d started in on Titans Volume 3 when I found a reference to the team’s battle with Deathstroke in the past tense. Had I missed something?

Turns out I had. But I picked up a big pile of these comics for a dollar each from the library’s overstock sale so I had the missing piece, which is this book. It didn’t have a number because it was part of what’s known as a “crossover event” involving a bunch of different titles, in this case Titans, Teen Titans, and Deathstroke.

This led me to the next question: Was all the build-up worth it?

No.

Basically what you need to know here is that one of Deathstroke’s kids, Grant Wilson, was recruited by H.I.V.E. (ahem: the Hierarchy of International Vengeance and Extermination), who gave him a serum that turned him into the supervillain Ravager but that ultimately brought caused him to have a heart attack while fighting the Teen Titans. Deathstroke sort of blames Grant’s death on the Titans, and decides he’ll use the Flashes’ (Flash and Kid Flash’s) ability to enter into the time force to go back into the past and save his son’s life. Since everyone knows disruptions in the space-time continuum always go wrong, the Titans and Teen Titans team up to stop Deathstroke. This they manage to do and Deathstroke, more disappointed than angry, decides to “retire” by setting up a new team of hero/villains composed of his other kids.

I don’t like most time-travel stories. This one doesn’t work for all the usual reasons. I particularly didn’t care for the blather trying to explain the mechanics of time travel. You see, Deathstroke modified an extractor made by someone for Flash to keep his speed power under control. Deathstroke uses this device to store that energy in battery cells connected to his fancy new “Ikon suit” (complete with lightning bolts!) that has a “gravity sheath” that allows him to move at near-light speed and enter the “time stream.” Then, when the Titans and Teen Titans want to follow Deathstroke they mimic his combination of Kid Flash’s super-speed and the gravitational properties of his costume by joining Jericho’s gravity sheath with Flash’s speed to create a “time vortex” stabilized by Raven’s “chrono-kinesis” and Starfire’s energy, all while being tethered by Raven’s mind-meld to the rest of the team as Flash goes running into the speed force, at least until Raven’s “vast mystical powers” begin to fray and her soul-self is in danger of being trapped in the “speed force,” which is where Deathstroke has looked into the face of God and achieved a higher consciousness.

Enough already. I lost interest in all of this long before the end. It all just seemed like a bunch of sparks and noise, with too many characters involved and not much for most of them to do but stand around barking at each other. Not that I knew who a lot of these people were anyway, or cared. I do know Deathstroke and have found him an interesting character in the past, but he’s a lot less so here, especially when he starts spouting scripture (a lot of scripture) in the epilogue. I think maybe there are fans who like this kind of story but it wasn’t my thing and by the time I finished I was glad that I was done with it, and nearly done with my Titans book haul.

Heading back to the old city of Suzhou again this week. After showcasing a bookmark from their modern museum, here’s one from their famous Lion Grove Garden, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The garden was built in 1342 by Buddhist monks, and has had to be rebuilt several times in the centuries since. It’s so named because the rock formations are supposed to look like lions, though from the pictures I’ve seen I think that’s a bit of a stretch.

Fun fact: The Suzhou Museum was designed by I. M. Pei. The Lion Grove Garden was previously owned by the Pei family, and I. M. Pei played in it when he was a child.

Book: The Dark Forest by Cixin Liu

This has the feel of a more traditional mystery, even though there wasn’t much of a tradition yet. A wealthy banker is given a beryl coronet, one of the “most precious public possessions of the empire,” as collateral for a loan. Not trusting to keep it in his bank’s safe, he takes it home with him and locks it in his dresser. Because that’s the kind of thing you did back in the day. He also makes sure to tell his niece and wastrel son what he’s doing. That night he discovers his son apparently in the act of stealing the coronet, and has him arrested by the police as a few gems from the coronet have gone missing.

After being told the story, Holmes is convinced that the son is innocent. He then proceeds to solve the case by the usual method of getting out his magnifying glass to examine evidence like footprints, going out on mysterious nighttime excursions, and employing “an old maxim of mine that when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” With regard to that final point, once again I didn’t find this maxim very persuasive, as Holmes never excludes what is impossible but only what is highly unlikely. Few things, after all, are impossible. But as I’ve criticized this maxim enough already, I won’t say more about it here.

I think it’s pretty obvious to most readers what’s going on, as once you’ve excluded the most likely suspect all we’re left with is the niece, who is an emotional girl with a habit of giving herself away. She’s not a bad person, but betrays her uncle the banker because she’s got a crush on a dissolute rake named Burnwell who is in need of money. She loves unwisely and too well. Or as Holmes unhelpfully explains to the uncle, “I have no doubt that she loved you, but there are women in whom the love of a lover extinguishes all other loves, and I think that she must have been one.” I mean, someone has to come first.

It’s a pretty good little mystery, even if nothing stands out about it. I did like how the rake who seduces the niece throws away the gems to a fence for such a low sum. No wonder he’s in such dire straits financially; he doesn’t know the value of anything. I’m afraid Mary has made a bad choice, which inverts the usual way one of these stories ends. And where is poor Mary now? “I think that we may safely say,” returned Holmes, “that she is wherever Sir George Burnwell is. It is equally certain, too, that whatever her sins are, they will soon receive a more than sufficient punishment.” Yikes!

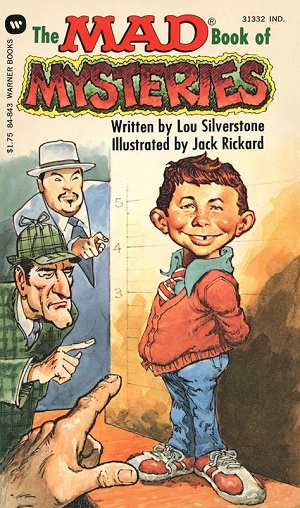

Since I’m a fan of both Mad Magazine and classic detective fiction, a book like this couldn’t really miss. I also like that it’s full of original stories and not a grab-bag of previously published material, and that all the stories have the same author and artist (Lou Silverstone and Jack Rickard, respectively).

Since I’m a fan of both Mad Magazine and classic detective fiction, a book like this couldn’t really miss. I also like that it’s full of original stories and not a grab-bag of previously published material, and that all the stories have the same author and artist (Lou Silverstone and Jack Rickard, respectively).

So the line-up of crime-solving all-stars here sounds like the cast of Murder by Death. There’s Hercules Pirouette, Archer Spillane Spayed, Shtick Tracer, Allergy Queen, Charlie China, Perry Maceface, and Shamus Holmes. And there’s also a spoof on G-Men movies now and then, a quick trip to Peanuts-land with Chuck Frown, Private Eye, and a bunch of gags about what cops say vs. what they really mean. Alas, there’s no Nero Wolfe or Miss Marple, though they’re on the back cover. I would have loved seeing them.

The gags aren’t terribly funny but Silverstone knows his stuff and the way he pokes fun at the material will make you smile. He takes digs at Poirot’s long, drawn-out and confusing explanations of the crime, and has Number One Son getting back at his dad for all the mean cracks made at his expense. But the style of humour is mainly geared around running a gag-a-page of snappy comebacks. When Shamus Holmes declares that a murder victim lived near a canal Dr. Whatso says “A canal? That’s eerie, Homes.” To which Holmes replies: “No, alimentary, my dear Whatso!” Because the deceased worked at a candy company you see.

Rickard often gives the supporting characters familiar movie-star faces. James Cagney and Robert Redford, for example, as their era’s representative G-Men. I loved the look of all the stories, though Mad‘s house style of square speech bubbles and sans serif lettering seemed out of place. I don’t know why they couldn’t have played around with that more. Lettering matters.

What I took away the most from revisiting this pocketbook today though is how much the cultural landscape has changed. In the late ‘70s-early ‘80s classic detective fiction could be sent up for a mass audience, here or in the aforementioned Murder by Death, because it could be assumed everyone had some familiarity with these characters. Today I think that kind of awareness belongs to a vanishing few older readers. To be sure, golden age detectives still have their cults, but they aren’t household names anymore. And what’s more, nobody has taken their place. Caricature exploits character, and the old guard had plenty of that. But how can you caricature Inspectors Morse, Rebus, or Gamache? They’re more realistic and psychologically grounded but not as memorable, and give satirists a lot less to work with.

My grandfather was a village postmaster, and my mother had fond memories of working at the post office with him when she was a kid. My father was a stamp collector, and while this wasn’t a hobby I stuck with I did have stamp albums as a boy that I’ve held on to, along with the boxes filled with my father’s highly eclectic (and I’m afraid not very valuable) collection.

When it comes to my affection for all things mail related, however, what stands out the most is the fact that I lived on a farm most of my life and we received rural mail delivery. I was always impressed by the job these people did, even in bad weather on what were the worst of roads. Living in rural isolation, the arrival of the mail was an event that meant a lot to family and neighbours.

But times change. When I was young there were few courier companies and no Amazon delivery vans (much less drones). There was no Internet and email. There were no flyers or junk mail. People sent Christmas cards. In other words, everything came to you through the mail, and if it wasn’t always something you wanted it was at least something you knew was important.

This is no longer the case, which is why Canada Post, the Crown corporation that handles the mail in this country, is facing such a host of problems. Chief among these problems is their high labour costs and the fact that a lot of what made the mail not only useful but essential is gone. The result is a corporation that is, according to one recent study, bankrupt. Apparently they lost $300 million in just the first quarter of 2025. That’s not sustainable.

Last year the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) went on strike for a month before being ordered back to work in the hope of finding a solution somewhere down the road. That solution hasn’t materialized and as I write this another strike is expected.

I don’t think anyone on either side, workers or management, is under any illusions as to how grim the future is for Canada Post. That said, I do think the mail has a future. I don’t mind that such a valuable service is operating at a loss. I still think a country, especially one as big as Canada, needs a public, national mail system. What has to be faced though is that a dramatic restructuring of the mail, what it does and how it does it, is going to be required.

And when I say restructuring what I mean primarily is contraction. I probably get more mail than most people. But I don’t need daily mail delivery. If they even cut delivery back to once a week I think I’d be fine.

I don’t know how workable this is, but there have been various studies done and other recommendations made that can be picked from. The bottom line though is that in order to avoid collapse some contraction in service will be necessary. I can’t see the current postal service with its over 70,000 employees surviving long.

There’s a lesson here for other sunset sectors of the economy. I’m thinking in particular of universities. These grew at an unreasonable rate during relatively good economic times, but even back in the 1990s there were reports on how necessary some contraction was. In a period of declining enrolments and now caps put on foreign students (the lifeline that was keeping a lot of higher education afloat in this country) I don’t see a bright future for many of these institutions. And again, the alternative to contraction is collapse: just keeping on doing things the way we have until the whole system breaks down. I know it’s become an expression that’s meant to trigger a fierce reaction, but at this point we have to learn how to manage the decline.