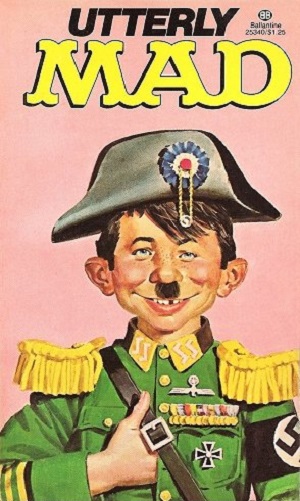

Utterly MAD

In my review of the Visions of Poetry edition of Poe’s “The Raven,” illustrated by Ryan Price, I mentioned how I had memorized the poem as a kid from a Mad magazine adaptation. Well, the book I read that adaptation in was Utterly MAD. I’ve kept it around a long time now.

In my review of the Visions of Poetry edition of Poe’s “The Raven,” illustrated by Ryan Price, I mentioned how I had memorized the poem as a kid from a Mad magazine adaptation. Well, the book I read that adaptation in was Utterly MAD. I’ve kept it around a long time now.

The stories collected here are mostly long-form satires of established properties like Robin Hood, Tarzan, Little Orphan Annie, and Frankenstein. And then there are a couple of cultural pieces, one on adapting novels to the big screen and the other on supermarkets. The latter I guess being something new at the time (the book’s first printing was in 1956).

Most of the humour hasn’t aged well. There are a lot of little gags that play out on the edges, but the verbal ones especially don’t land. Plus I think you’d probably want to be acquainted with the source material. “G. I. Shmoe” is a take-off, I think, of a G. I. Joe comic, but I didn’t get the punchline every woman delivers where they ask him if he’s got gum. And “Little Orphan Melvin” won’t work unless you have some idea of the original characters, how they talk and relate to one another, and the sorts of situations Annie finds herself in. Other stories, like “Robin Hood” and “Melvin of the Apes” just weren’t funny. Maybe they thought the name Melvin was funny. Also the Yiddish word “fershlugginer.” Sometimes the crammed visual style does work passably well, as with the “Frank N. Stein” story and the trip to the supermarket, but overall it wasn’t working for me.

That said, I love this little paperback for two stories that, for whatever reason, have stayed with me. Obviously one is the adaptation of “The Raven.” This is typical of the crammed style I mentioned, with lots of different stuff going on in every cell, including a lot that’s totally unrelated to the poem, like a dog that outgrows the narrator’s apartment. But where I give them the most credit is in including the full text of the poem and having all kinds of fun with it, from emphasizing the fearfulness of the narrator, hiding in his room, to presenting the lost Lenore as a beefy, cigar-smoking lady who presses clothes. To some extent, I’m still not sure how much, this interpretation of the poem has for me become a part of it that I can no longer disentangle from what Poe wrote.

The second story that stands out is “Book! Movie!” This is meant to illustrate how Hollywood takes gritty, realistic novels and cleans them up, turning them into tinselly trash. Which is something that I think probably happened a lot more often in the 1950s than it does today. Anyway, the Book part tells the story of a loser living in terrible poverty who cheats on his wife and is caught by a blackmailer (though I don’t know what the blackmailer could be thinking he’d get out of it). The guy then kills his mistress and the blackmailer (with lots of “Censored” dots covering up the gouts of gore) and is pursued by demons back to his home, where he learns that his wife, who he hates, has invited her twin sister to live with them “forever.” The man collapses in despair, saying: “This miserable hopelessly hopeless situation is just perfect for a book ending.”

The Movie part turns the man and his wife into an affluent couple who even sleep in separate beds. As was the custom on screen at the time. The man is pursuing an affair (because he can’t stand that his wife is a slob), and is caught by a blackmailer. He then kills his mistress and the blackmailer with a revolver, which mysteriously doesn’t leave any traces of blood (the man in the Book story had used a knife). Returning home, his wife runs to his arms and says that from now on she’ll be a perfect helpmeet and keep a tidier house, and they skip off together over the rainbow while singing about joy.

As I say, I think this phenomenon of the Hollywoodized/sanitized novel is probably not as big a thing today, but the outline presented here has always stuck with me as a way of thinking about how page-to-screen adaptation works.

As for the cover, I’m not sure how well it would fly in the present age. Probably a little better than Token MAD, and in both cases I’m hoping the sense of irony would help it out.