Over at the New Yorker the columnist David D. Fitzpatrick has just done a much-discussed forensic accounting (“How much is Trump pocketing off the Presidency?”) calculating the amount of money Donald Trump has made out of being president. The total he comes to, and this is presented as a conservative estimate, is $3.4 billion. Already.

Many payments now flowing to Trump, his wife, and his children and their spouses would be unimaginable without his Presidencies: a two-billion-dollar investment from a fund controlled by the Saudi crown prince; a luxury jet from the Emir of Qatar; profits from at least five different ventures peddling crypto; fees from an exclusive club stocked with Cabinet officials and named Executive Branch. Fred Wertheimer, the dean of ethics-reform advocates, told me that, “when it comes to using his public office to amass personal profits, Trump is a unicorn—no one else even comes close.” Yet the public has largely shrugged. In a recent article for the Times, Peter Baker, a White House correspondent, wrote that the Trumps “have done more to monetize the presidency than anyone who has ever occupied the White House.” But Baker noted that the brazenness of the Trump family’s “moneymaking schemes” appears to have made such transactions seem almost normal.

When thinking about numbers like this I think it’s helpful to remember just how much a billion dollars is. A million seconds is approximately 11.5 days, while a billion seconds is about 31.7 years. The scale of Trump’s corruption isn’t just unparalleled, it’s nearly unimaginable.

Who knew this level of profiteering was going to happen? Everyone! Including yours truly, in my immediate post-election post in November 2024:

The main thing I feel confident predicting though is that we are going to see kleptocracy run mad. The looting of the American state is about to begin, on a scale (to borrow a favourite Trumpism) never before seen in the history of the world. Back during his first term Sarah Kendzior characterized the Republican plan for America as being to “strip it for its parts,” and Trump presided over an administration more corrupt and indeed criminal than any the U.S. had ever experienced. Well, expect that to ramp up bigly. The copper wires are going to be ripped from the walls, the plumbing fixtures torn out, and the lead taken from the roofs. Switching metaphors, the cookie jar is going to be wide open and sitting out on the table for at least the next two years.

As the corruption has mounted, here are some other voices (all emphases in bold added). Just to anticipate a couple of complaints in advance:

These are all liberal media sources. If you define liberal as any voice speaking out against Trump, yes they are. But the facts are out in the open.

It’s just the same as what Democrats did (and do) when they’re in power. Not like this! To be sure, corruption is very much part of modern politics. But nothing has been done on the scale of what Trump is doing.

So without further ado:

From “Trump’s Corruption” by Jonathan Rauch (The Atlantic, February 24 2025):

Patrimonialism [the form of government Rauch identifies Trumpism with] is corrupt by definition, because its reason for being is to exploit the state for gain—political, personal, and financial. At every turn, it is at war with the rules and institutions that impede rigging, robbing, and gutting the state. We know what to expect from Trump’s second term. As Larry Diamond of Stanford University’s Hoover Institution said in a recent podcast, “I think we are going to see an absolutely staggering orgy of corruption and crony capitalism in the next four years unlike anything we’ve seen since the late 19th century, the Gilded Age.” (Francis Fukuyama, also of Stanford, replied: “It’s going to be a lot worse than the Gilded Age.”)

They weren’t wrong. “In the first three weeks of his administration,” reported the Associated Press, “President Donald Trump has moved with brazen haste to dismantle the federal government’s public integrity guardrails that he frequently tested during his first term but now seems intent on removing entirely.” The pace was eye-watering. Over the course of just a couple of days in February, for example, the Trump administration:

gutted enforcement of statutes against foreign influence, thus, according to the former White House counsel Bob Bauer, reducing “the legal risks faced by companies like the Trump Organization that interact with government officials to advance favorable conditions for business interests shared with foreign governments, and foreign-connected partners and counterparties”;

suspended enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, further reducing, wrote Bauer, “legal risks and issues posed for the Trump Organization’s engagements with government officials both at home and abroad”;

fired, without cause, the head of the government’s ethics office, a supposedly independent agency overseeing anti-corruption rules and financial disclosures for the executive branch;

fired, also without cause, the inspector general of USAID after the official reported that outlay freezes and staff cuts had left oversight “largely nonoperational.”

By that point, Trump had already eviscerated conflict-of-interest rules, creating, according to Bauer, “ample space for foreign governments, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, to work directly with the Trump Organization or an affiliate within the framework of existing agreements in ways highly beneficial to its business interests.” He had fired inspectors general in 19 agencies, without cause and probably illegally. One could go on—and Trump will.

From “The Trump Presidency’s World-Historical Heist” by David Frum (The Atlantic, May 28 2025):

Nothing like this has ever been attempted or even imagined in the history of the American presidency. Throw away the history books, discard people, comparisons to scandals of the past. There is no analogy with any previous action by any past president. The brazenness of the self-enrichment resembles nothing seen in any earlier White House. This is American corruption on the scale of a post-Soviet republic or a post-colonial African dictatorship.

The Trump story . . . is almost too big to see, too upsetting to confront. If we faced it, we’d have to do something – something proportional to the scandal of the most flagrant self-enrichment by a politician that this country, or any other, has seen in modern times.

From “Follow the money: Trump’s corruption hits shocking heights” by Juan Williams (The Hill, June 2 2025):

Right now, it is hard to miss what looks like a deluge of pocket-lining as private money swirls around this president. And let’s not mention the free airplane he is ready to accept from a foreign power.

The money grab is so breathtaking that it has left Trump’s critics muttering expletives while the normally reliably loud critics of government corruption, especially congressional Republicans, appear in stunned silence.

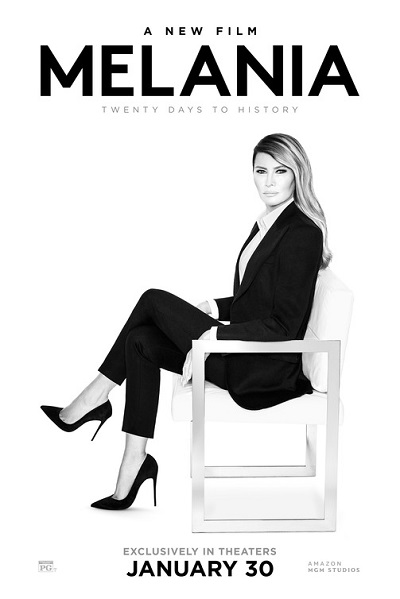

Even as Trump’s administration seeks to regulate crypto more loosely, his jaunt into crypto — his $TRUMP and $MELANIA meme coins, plus his stake in World Liberty Financial — has reportedly increased his family’s wealth by billions in the last six months and now accounts for almost 40 percent of his net worth.

New York Times reporter Peter Baker posted on X last week, “Trump and his family have monetized the White House more than any other occupant, normalizing activities that once would have provoked heavy blowback and official investigations.”

Presidential scandals of the past seem quaint by comparison — Hillary Clinton’s cattle futures, Eisenhower’s chief of staff resigning over a coat, Nixon stepping down over a “third-rate burglary.”

The magnitude of Trump’s self-serving actions to enrich himself exceeds anything in our history. Nixon sought distance from wrongdoing, telling Americans that he was “not a crook.” He wanted to be clear that he did not personally gain money from any abuse of power that took place in his administration.

Trump makes no effort to proclaim his innocence as he pursues wealth while in public office. And while Nixon held power during a time of relative economic calm for the middle class, Trump is acting against a backdrop of economic anxiety for most Americans.

From “This is the looting of America: Trump and Co’s extraordinary conflicts of interest in his second term” by Ed Pilkington (The Guardian, June 16 2025):

Trump and his team of billionaires have led the US on a dizzying journey into the moral twilight that has left public sector watchdogs struggling to keep up. Which is precisely the intention, said Kathleen Clark, a government ethics lawyer and law professor at Washington University in Saint Louis. . . .

“People talk about ‘guardrails’ and ‘norms’ and ‘conflict of interest’, which is all very relevant,” she said. “But this is theft and destruction. This is the looting of America.”

Trump returned to the White House partly on his promise to working-class Americans that he would “drain the swamp”, liberating Washington from the bloodsucking of special interests. Yet a review by the Campaign Legal Center found that Trump nominated at least 21 former lobbyists to top positions in his new administration, many of whom are now regulating the very industries on whose behalf they recently advocated.

Eight of them, the Campaign Legal Center concluded, would have been banned or restricted in their roles under all previous modern presidencies, including Trump’s own first administration.

Final thoughts: the one thing that surprised Fitzpatrick the most in his investigations is the frantic pace at which Trump and his family are exploiting the office of the presidency to line their pockets. So keep in mind we’re only 8 months in and the number is going to keep going up, perhaps at an even accelerated pace. Also: the guardrails against corruption have been entirely torn down and with all the bodies meant to keep an eye out for such behaviour and even call it to account either disbanded or staffed with figures whose only loyalty is to Trump, it’s now become a free-for-all. In terms of high-level graft and corruption the U.S. is effectively a lawless state, already experiencing a level of profiteering, in terms of the dollar amounts involved, unparalleled by any modern government, with the possible exception of what happened after the breakdown of the Soviet Union and the rise of the Putin-era oligarchs. America’s oligarchs took notes on that, and are on board for the same ride. I mean, they already got a $3 trillion dollar-plus tax cut (conservatively estimated) in the Big Beautiful Bill. That’s trillion. Or, to use my earlier analogy, 31, 689 years. The mind boggles.

And now they have crypto to play with too.

So my next totally predictable prediction: the looting of America is going to get worse.