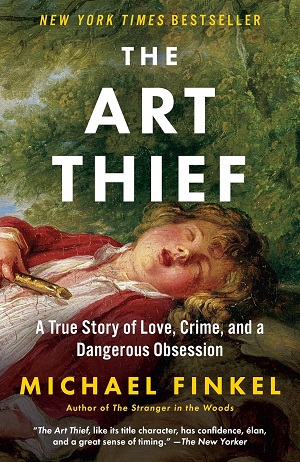

The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession

By Michael Finkel

The crime:

From 1994 to 2001 Stéphane Breitwieser had a career as “one of the greatest art thieves of all time.” Usually in the company of his girlfriend Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus he stole nearly 250 works of art from over 170 museums in France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands. He didn’t try to sell any of the items but kept them in the attic apartment in his mother’s house that he lived in with Anne-Catherine. While in prison after he was caught his mother threw many of the sculptures he’d stolen in the nearby Rhône-Rhine Canal (from where they were later recovered) and burned the paintings.

I don’t think I’d ever heard of Stéphane Breitwieser before this, but according to Michael Finkel, who I have no reason to doubt, he was one of the most prolific art thieves in history. That he didn’t consider himself to be an art thief but rather an “art liberator” or “art collector with an unorthodox acquisition style” was just a kind of criminal casuistry, though it is fair to say that he was a different kind of art thief. Whatever other lies and rationalizations Breitwieser gave for his looting of so many priceless treasures, it’s clear he didn’t do it for the money. And this despite the fact that he had no money of his own, only working odd, minimum-wage jobs like waitering or pizza delivery while sponging off of his mother and grandparents and collecting government welfare payments. It was the kind of life that, in addition to fostering his narcissism and sense of entitlement, freed him on a more practical level from caring about making a living and allowed him to spend most of his time doing what he loved.

At this point I want to step in and reassert a point I never tire of making: that for almost any criminal, or wicked person, to be successful they need help. Here’s how I put it in my review of A Plot to Kill:

Bad people are everywhere. But all too often the people who escape blame are their enablers.

…

It is not enough, to use the old line often misattributed to Edmund Burke, that for evil to succeed all that is necessary is for good men to do nothing. Evil needs a hand. Evil needs its suckers, dupes, and people who just want to be in on whatever the scam is because they think there’s something in it for them.

The question of to what extent Anne-Catherine was Breitwieser’s partner-in-crime remains open. Probably more than she let on, but perhaps not a lot more than just being a lookout. More interesting, and stranger, was the relationship between Breitwieser and his mother. To some extent she was his chief enabler. For starters she allowed him to live in her house, which is where he stored all his loot, turning it into an attic “treasure chest” or cave of Ali Baba. At least to some extent she must have known what was going on, but preferred to turn a blind eye. And then, after her son (her only child) was finally captured, she took it upon herself to destroy or attempt to destroy all the evidence. Out of hate, she told the court, but more likely out of love. With reference to this final crime, a French prosecutor would declare that “She is the central figure in this horrific disaster, the person who should be held most accountable.”

I couldn’t help thinking of a criminal type I’ve identified as “the boys in the basement.” I did a post on this phenomenon here, and a follow-up here. What I was addressing in these posts was the number of cases where young men who became mass murderers were often found to have mothers who appeased, accommodated, and enabled them into a kind of adult babyhood. In many cases the mothers in question shared a lot of similarities, for example being divorced, professional care-givers who seemed to enjoy keeping their adult children at home. Mireille Breitwieser (née Stengel), divorced, had been a nurse specializing in child care (Anne-Catherine, perhaps not coincidentally, was a nurse’s assistant). In a description of a videotaped interaction between mother and son Mireille appears as a submissive servant for him to boss around, and I find it telling that she even continued to cook dinner for him all the time he was living in her house. Breitwieser himself admitted he was “spoiled rotten,” and a state psychiatrist assessed him as remaining “immature.” “Coddled by a mother who caters to his whims,” another doctor opined, he had remained (in Finkel’s paraphrase) “a brat.” One suspects Anne-Catherine finally broke up with him not because of his dangerous kink (that is, stealing precious works of art) but rather just because he was never going to grow up. His mother had a firmer hold on him than she ever would.

In sum, while Stéphane doesn’t tick all the boxes for a boy in the basement, as a “boy in the attic” I think he belongs in the same discussion.

Moving further into the psychodrama, Finkel spends some time speculating on the exact nature of Breitwieser’s obsession. Was the compulsion he felt to steal works of art, and it was a compulsion, a kind of kleptomania? One psychiatrist says no, as kleptomaniacs typically don’t care about the specific objects stolen, and their thefts are followed by feelings of regret and shame. Was he a case of Stendhal syndrome? No, because that was only a nineteenth-century literary conceit anyway.

Was he an extreme kind of aesthete? That was his own diagnosis: “Breitwieser’s sole motivation for stealing, he insists, is to surround himself with beauty, to gorge on it. . . . He takes only works that stir him emotionally, and seldom the most valuable piece in a place.” And if that sounds a bit sexual I don’t think that’s by accident. Stealing was, in its mix of compulsion and addiction, akin to sex, and the stolen objects had their own sort of afterglow that he liked to bask in back in the attic, placing favourites next to his bed. Or, better yet, “So many great works of art are sexually arousing that what you’ll want to do, Bretiwieser says, is install a bed nearby, perhaps a four-poster, for when your partner is there and the timing is right.”

I don’t know if there’s any way to sort this out. I like Finkel’s conclusion that Breitwieser more closely resembles the people we know who have made careers out of stealing books than he does a typical art thief (“In the taxonomy of sin, Breitwieser and Anne-Catherine belong with the book thieves”). And seeing collecting as an obsessive-compulsive disorder is also valid. What’s fair to say is that Breitwieser truly was passionate about art and that he felt absolutely compelled to steal it. He literally couldn’t stop himself, even in situations where he knew he wasn’t just being risky but stupid.

But for years he stayed lucky. Sure, he was good at what he did. He had several qualities that proved indispensable: confidence, dexterity, and the ability to stay calm under pressure, to think fast and improvise when he met with obstacles. Because he mainly targeted smaller, local museums those obstacles weren’t insurmountable. The works he “liberated” weren’t that difficult to snatch. Alarms seem rarely to have been in place, and the slicing of the silicone glue at the edges of a Plexiglas case or the undoing of a few screws was often all it took.

As for the security guards, I don’t want to trash people who are already the butt of so many jokes. In fact, the purpose of a security guard is mostly to act as a “visual deterrent.” Meaning that the site of them is supposed to scare would-be criminal types off. Not because a guard is a physical threat, but because they are potential witnesses. They are usually young people or retirees, with little to no training, and not very motivated because they’re making minimum wage. The hardest part of the job is fighting off boredom or just staying awake. Breitwieser had actually been a guard at one point so he knew they didn’t pose much of a challenge.

The final factor in Breitwieser’s spectacular run of success was luck. Everything just seemed to go his way, even when he was caught once in Switzerland and allowed to walk. But these things catch up with you. As Finkel puts it: “No one gets away with bold crimes for long. Luck always runs out, it’s inevitable.” After a spectacular run, Breitwieser’s luck turned against him in a big way. It was only a series of unfortunate (for him) events that led to his capture. After stealing a bugle from the Wagner Museum in Switzerland, Anne-Catherine insisted on returning to the scene of the crime so she could erase any fingerprints he might have left. She wants to go alone but he insists on driving her. She tells him to stay in the car but he gets out and goes for a walk around the grounds. He is spotted by an old man walking a dog who had noticed him the day before. The police arrive and take him away.

By this point, however, Breitwieser may have just been growing tired of the game, no longer pursuing particular works of art out of some great passion but just grabbing items in a lazy and opportunistic way. At the end, Anne-Catherine would tell investigators, “his stealing had become ‘dirty’ and ‘maniacal.’ His aesthetic ideals about idolizing beauty, treating each piece as an honored guest, have descended into hoarding.” He treats the stolen works carelessly, damaging and even destroying them. The joy is gone. You have the sense in the end that he was only going through the motions, his addiction having reduced him to an automaton.

It’s often at this stage in any criminal spree that it’s suggested that the perpetrator, perhaps subconsciously, wants to be caught. I don’t think that’s what was happening here, but there may well have been something of the “rule of ten” I’ve written of before going on. Breitwiester wasn’t a professional thief. It wasn’t his job and he seems to have been a genuinely lazy fellow with a poor work ethic anyway. For him I think it was a sort of release of youthful energy, sexual or otherwise, and after six or seven years that energy had pretty much run its course.

The Art Thief is a really good book, well written, insightful, and a quick read. My only complaint would be that the full-colour photo section only contains pictures of some of the items Breitwieser stole. There are no pictures of Breitwieser or any of the other people in the book, or of the museum rooms he stole from, which I think would have been interesting. Leaving that one caveat aside, Finkel’s telling of the story also benefits from the ten years he spent covering it. That long a gestation allows for some distance, which is something I think most veteran readers of true crime appreciate. This isn’t a timely book meant to cash in on a sensational trial that’s making headlines. It has the luxury to be more reflective.

I also thought Finkel did a great job navigating the sources to come up with an objective account. This was all the harder as Breitwieser talked a lot. He allowed himself to be interviewed by Finkel and indeed even wrote his own book about his life as an art thief. His side of the story is all out there. But the women in his life, his mother Mireille and girlfriend Anne-Catherine, haven’t said anything to anyone. Some of the stolen pieces were never accounted for. Do either of them know what happened to them? How much did they know about what Breitwieser was doing? Everything? More, I’m sure, than they were willing to let on. “I am stupefied by her perjury,” one prosecutor declared in court about Anne-Catherine’s testimony. But by that time both women had gone into lockdown. I doubt interviewing them would have revealed much, but I was left with the sense that this is where the real story was.

Noted in passing:

While in prison in Switzerland Breitwieser does not “shower nude like everyone else,” but rather “washes in his underwear.”

I’m not sure why Finkel tells us this but I’m glad he did because it lets me talk about something that’s been bothering me for a while.

I grew up playing sports, and in particular was on the swim team both in intercity competitions and in high school. That meant spending a lot of time in locker rooms and in group showers. Everybody got naked. In the years after high school I became a bit of a gym rat and have almost always had a membership at a fitness club wherever I’ve lived.

Up until the COVID-19 shutdown in 2020 showering was as it has always been. You showered in the nude. Every now and then you might see someone showering in their underwear but this was very rare. And in the sauna or steam room you wrapped a towel around your waist, but otherwise that was it. Even if you were shy, there was no real need for modesty at the gym where I work out because the showers are all individual cubicles with closing doors. You’re all by yourself in there, and you can wrap yourself in your towel when you come out.

When the pandemic shut all the gyms down I took the next four years off, only returning in 2024. And I immediately noticed that norms had changed, dramatically. It is now the case that very nearly everyone is showering in their underwear. Everyone! Every now and then you might still see someone (like me) showering in the nude, but they are the exceptions. Just the day before posting this review a young fellow, I would say just into his early 20s, came out of the showers in his shorts and his t-shirt, soaking wet. I couldn’t believe it. Five years ago I think I would have asked him if he was OK. Now I was just glad he’d taken his shoes and socks off.

What has led to this change in behaviour? And how did it happen so rapidly? I note that it’s a practice that’s been adopted by men of all ages, from the very young to the very old. Are they watching so much porn that they feel body-shamed at only being average? I honestly can’t say. What I can say is that I think the whole idea of taking a shower while wearing clothes is ridiculous.

Takeaways:

With the high cost of housing more and more adult children are living with their parents out of necessity. And in some cultures this can even be a good thing, with intergenerational support working both ways. But a mother enabling or coddling a man-baby is always a bad idea, damaging to both parties. It usually turns into a poisonous and perverted love-hate relationship, with the family home becoming a nursery of vice.

Are the chaps in shorts and t shirts in cubicle showers or in an open shower?

LikeLike

Cubicles! With doors! I just don’t know what’s going on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s just plain bonkers.

LikeLike

It’s bonkers and it’s now normal! I don’t understand the world anymore.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Too bad he didn’t try to steal the Bear Pope’s hat. The BP would have ended his career like that!

If you have a stall, why in the world would anyone wear underwear? And a t-shirt? That just boggles my mind. All I can think is how mouldy it all is going to get…

LikeLike

It is both weird and, now, normal. At least the underwear. Wearing your shorts and a t-shirt in the shower was a new one.

The art thief focused on northern renaissance art, so the BP’s hat would have been safe. But maybe not his honey pot.

LikeLiked by 1 person