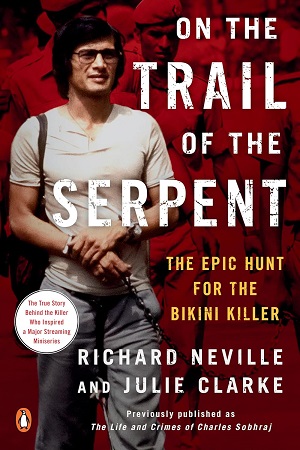

On the Trail of the Serpent: The Epic Hunt for the Bikini Killer

By Richard Neville and Julie Clarke

The crime:

Charles Sobhraj was the child of an Indian father and Vietnamese mother born in Saigon in 1944. He took early to a life of petty crime and ran afoul of the law a lot as a juvenile. When his mother moved to France with a new partner Sobhraj went with her and got into trouble there as well. Ingratiating himself with various enablers, he left France and became an itinerant crook involved in a bunch of different scams in South-East Asia. He seems to have mainly been involved in gem and drug smuggling, and would often drug Europeans to rob them and steal their passports. For some reason, and this is the great mystery, Sobhraj’s criminal career took a much darker turn in the mid-1970s as he went on a killing spree while living in Bangkok, mainly targeting European tourists on the so-called “hippie trail.” He killed at least 12 people but perhaps twice that many. He was finally arrested in 1976 and imprisoned in India. He escaped from prison, though perhaps only to be rearrested so that he would not be extradited to Thailand, where he faced the death penalty. After serving his time in India (and with the statute of limitations on his crimes in Thailand having passed) he was set free and enjoyed a life of minor celebrity in France but in 2004 he was re-arrested while visiting Nepal (where he had also murdered a pair of tourists). In 2022 he was released from prison in Nepal on account of his age and good behaviour and now lives in France.

This is a 2021 update of a book that came out in 1979 under the title The Life and Crimes of Charles Sobhraj. That was actually a better, or at least more accurate, title. I don’t recall any mention here of Sobhraj being called “the Serpent,” and the sobriquet “bikini killer” was only something he picked up because that’s what one of his victims was wearing when her body was found.

I suspect the book was reissued (and so retitled) in part to cash in on the spark of interest created by the 8-part BBC series The Serpent that came out in 2021. But an epilogue also brings the case up to date on Sobhraj’s later convictions and imprisonments. Though not totally up to date, since it leaves off with Sobhraj still in a Nepalese prison.

It’s likely to remain the standard work on Sobhraj then, as it’s quite well written by a pair of authors who seem to have really understood the milieu (Neville had authored an early guidebook to the hippie trail) and who had also interviewed Sobhraj extensively. This really helps because it’s a very complicated story that even now remains shady in several places. But Neville’s familiarity with Sobhraj is also problematic, which is something that Clarke (his wife as well as co-author) flags.

The thing is, Sobhraj was an accomplished con and a fraud before he was a killer and he had charm to burn. And he wasn’t just a natural but made a study of it, constantly reading books on psychology and how to influence (read: manipulate) people. So Clarke was right to feel nervous about Neville being played, which is something I think Sobhraj was definitely trying to do. But it’s also something that as readers we have to be on guard against, because so much of the story as we have it comes from Sobhraj himself. His besotted French-Canadian lover Marie-Andrée Leclerc died in 1984. His accomplice Ajay Chowdhury was last seen in 1976, with most people believing that Sobhraj killed him around that time. Add to this the fact that Sobhraj was a fluent and congenital liar, with a great deal to lie about, and parts of the story will likely always remain pretty murky.

The most obvious question, which I flagged earlier, relates to motive. Why did Sobhraj become a prolific murderer so suddenly? Usually in such cases there is a history of slow escalation. But that’s mostly with sexual serial killers and one of the distinguishing features of Sobhraj’s murder spree is that sex was not a driver. He seems to have killed as many men as he did women and I don’t think there was any evidence of sexual assault being involved. Nor does there seem to have been much if anything in the way of a financial motive. Sobhraj was certainly a thief, but seems to have made a good living off of whatever scam he was working or just drugging his victims and tossing their rooms for money, jewelry, and passports. So why did he go through the difficult process of killing so many people and then having to dispose of their bodies?

Sobhraj’s own story was that he was operating on orders given from drug cartels based in Hong Kong, who wanted him to get rid of rogue mules. Or at least that’s how I understand it. I don’t think this makes any sense at all, however, and the accounts Sobhraj gave of several of the killings didn’t match up with what we know, especially with regard to the timelines. I agree with the opinion of Herman Knippenberg, the Dutch diplomat stationed in Thailand who did so much to hunt Sobhraj down, that the hit-man explanation was “pure cant.” I would say the same about Sobhraj’s (much later) claim that he was fighting a kind of anti-colonial struggle against Western exploiters, represented by the young backpackers on the hippie trail. To be sure, he probably did feel some resentment toward Europeans in general, and the book adverts to that.

But this doesn’t explain why he started killing so many people in the mid-1970s, and I think it’s more likely that he just didn’t care for anyone very much, including members of his immediate family. And when I say he didn’t care for them I only mean he thought they were disposable, not objects of obsessive hate. It’s typical of a lot of hardened criminals that they have a near complete lack of empathy, and what’s more disturbing than the passion killers are the ones who would just as soon kill you as look at you. The lives of others, and their suffering, mean nothing to them.

I think Knippenberg gets closer to the truth when he suggests that Sobhraj just couldn’t stand the thought of anyone drifting out of his control. In her epilogue, published after Neville’s death in 2016, Clarke talks about how Sobhraj “ticked every box in the Hare Psychopathy Checklist”:

Glib and superficial charm; grandiose (exaggeratedly high) estimation of self; need for stimulation; pathological lying; cunning and manipulativeness; lack of remorse or guilt; shallow affect (superficial emotional responsiveness); callousness and lack of empathy; parasitic lifestyle; poor behavioral controls; sexual promiscuity; early behavior problems; lack of realistic long-term goals; impulsivity; irresponsibility; failure to accept responsibility for own actions; many short-term marital relationships; juvenile delinquency . . . criminal versatility.

Sobhraj, she concludes, “is the perfect psychopath.” And it’s true he really did cover all of the bases. One thing that’s left out of this checklist, however, is his need to control others. Maybe this is the flipside of the lack of personal control (among his other self-destructive habits, Sobhraj was a compulsive gambler), and maybe it comes with his narcissistic power-tripping. But however you explain it, he seems to have got some psychological satisfaction out of getting people to rely on him, submit to him, and even blindly follow him into some very dark places. I don’t think he ever loved any of the women he seduced, but his ego reveled in how much they adored him. Just before his arrest Marie-Andrée wrote in her diary “I love him so much that I can only make one being with him. I can only exist because of him, I can only breathe because of him. And my love is increasing.” This was well after she realized that she was “just an employee satisfying his whims” and even after when she must have known he was a serial murderer and after he had long been physically abusing her as well. This sort of toxic love, if you can call it that, is a drug, and it’s bad for everyone.

So, to round out the point I raised earlier, Clarke had good reason to suspect Sobhraj was working his charm on Neville while being interviewed. And there were places in the text I could see that happening. Indeed, Sobhraj has continued to cast his spell, as his sickening celebrity has continued even up to this day. It’s a point I’ve made over and over again in these True Crime Files, and elsewhere as well: Wicked people are limited in what they can achieve on their own. They need enablers. Sobhraj’s criminal career highlighted this phenomenon. Like most such operators he had a kind of sixth sense for their weakness, most evident here in the devotion of “Alain Benard” (the pseudonym given Felix d’Escogne) a soft-hearted and soft-headed prison volunteer he charmed while incarcerated as a youth in France. And later he was always surrounded by a gang of flunkies under his spell, without whom he couldn’t have operated. Yes, some of them were victims too, but we can’t let such people off that easy.

Noted in passing:

When escaping from jail in Afghanistan Sobhraj drugged his guards with sleeping pills and had to calculate a dosage based on the fact that “They were big men, more than six feet, like most Afghans.”

This surprised me enough to want to check it out. According to the most recent statistics I could find online the average height of an Afghan male is 5’6”, which ranks them in the bottom quartile of all nations. I’m sure there are regional and tribal differences, but still this is quite a miss.

I’m not sure if it was a lack of feeling that led Sobhraj to keep a pet gibbon monkey named Coco in a cage on the balcony of his Bangkok apartment. It might have been more the custom at the time. It struck me as very sad though, especially as the only time it gets referenced is when a neighbour spies it sitting in its cage “with its head in its hands” just before it is found dead one morning. Marie-Andrée then accuses one of the itinerant residents, who Sobhraj was poisoning, of poisoning the monkey. More likely, Sobhraj was using it as a guinea pig. But keeping a monkey in a cage in your apartment even without testing drugs on it just struck me as terribly cruel.

Takeaways:

You can’t spell charm without harm. If you meet someone you suspect of being charming you should at the very least be on your guard. They’re never up to any good.

That last sentence are wise words to live by. That’s why I try to be a jackass to everyone I meet.

😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I think maybe it’s my own lack of charm that makes me suspicious of these types. Charm is a dangerous weapon and should be treated as such.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Have no fear, you’re a real jackass!

😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I know that coming from you that means something.

LikeLiked by 2 people

No fake, glib smackdowns from me. You can always trust me to say it like I see it. And if you ever need a safehouse to put all your money in, I’m here for you man!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not a nice chap then. Mad that he kind of gets away with it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, he really worked the system and it’s sickening that he got out early. He seemed able to con everyone.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What should I do if someone starts being charming to me? Call the cops?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Give them a Glasgow kiss of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s instead of a welcome handshake.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’ll keep it in reserve for charming welcomers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Depends on the situation. Is this in a steam room? A sauna?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are these places where people usually try to charm you?

LikeLike