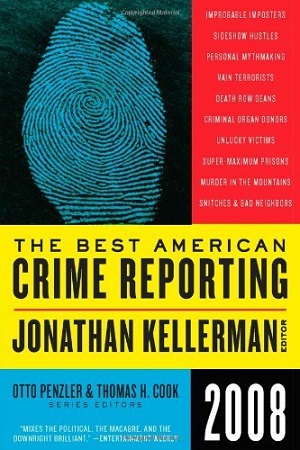

The Best American Crime Reporting 2008

Ed. by Jonathan Kellerman

The crimes:

“The Story of a Snitch” by Jeremy Kahn: snitches get stitches, or in Baltimore they’re shot multiple times and left for dead.

“A Season in Hell” by Dean LaTourrette: an American finds himself on the wrong side of the criminal justice system in Nicaragua.

“I’m with the Steelers” by Justin Heckert: claiming to be a member of the Steelers (an NFL team) gives a boost to a romance scammer living in Pittsburgh.

“The House Across the Way” by Calvin Trillin: a fight between neighbours on a New Brunswick island gets nasty.

“The Caged Life” by Alan Prendergast: Tommy Silverstein spends a very long time in isolation.

“Badges of Dishonor” by Pamela Colloff: the case of a pair of border guards who shoot an illegal and then try to cover it up becomes a political football.

“Dangerous Minds” by Malcolm Gladwell: the “science” of criminal profiling may only be a parlour trick.

“Dean of Death Row” by Tad Friend: a profile of Vernell Crittendon, who was in charge of executions at San Quentin for thirty years.

“The Tainted Kidney” by Charles Graeber: serial killer Charles Cullen (whose crimes were covered by Graeber in more depths in The Good Nurse) wants to donate a kidney. This turns out to be more difficult than it would be in, say, China.

“The Ploy” by Mark Bowden: army interrogators track down an al-Qaeda leader in Iraq by interviewing people connected to him.

“Day of the Dead” by D. T. Max: author Malcolm Lowry died after drinking heavily and taking a bunch of barbiturates. His wife may have helped him along.

“Just a Random Female” by Nick Schou: the capture of serial killer Andrew Urdiales.

“The Serial Killer’s Disciple” by James Renner: child murderer Robert Buell is executed, protesting up until the end that he was innocent of one of the murders he’d been implicated in. James Renner suggests Buell’s nephew may have had some responsibility for that one.

“Mercenary” by Tom Junod: the security manager at a nuclear power plant in Michigan imagines a fantasy life as a super-soldier.

“Murder at 19,000 Feet” by Jonathan Green: Tibetans looking to escape China by crossing over the Himalayas are shot by border guards, but the incident is viewed, and filmed, by Western mountaineers.

I’ve talked before about how I’m a big fan of this series, and how disappointed I was that it was cancelled. That said, I found this to be one of the weaker entries. For starters, there were a few stories I don’t think I would have included, for various reasons. One outlier would be acceptable, but even though true crime is a big tent I wouldn’t have included the Malcolm Lowry story here (which is just speculation), or the stories about the security manager who is a fabulist, the army “gators” at work, or the Chinese border incident. That’s not to say they aren’t good reads – I found “Mercenary” to be particularly intriguing – but I just didn’t think they belonged here.

I also didn’t think any of the stories stood out as being particularly memorable, aside from maybe Malcolm Gladwell’s critique of the science of criminal profiling. I even remembered much of that one from when I first read it in the New Yorker almost twenty years ago. I’m no fan of Gladwell, not even a little bit, so you can take it from me that it’s a piece worth checking out. Though his take really isn’t original. Indeed, it draws on a lot of work that had been done in the field, and various other true crime writers and reporters had been saying similar things. By coincidence, in one of the other pieces collected here, “The Serial Killer’s Disciple,” the police go to the FBI to get some help hunting a killer preying on young girls. I’ll let Renner tell the story:

The FBI commissioned a criminal profile of the perpetrator by Special Agent John Douglas, whose pioneering studies of the habits of serial killers inspire the book The Silence of the Lambs. Krista’s killer should be in his early to late 20s, Douglas said. He is a latent homosexual.

“When employed, he seeks menial or unskilled trades,” wrote Douglas. “While he considers himself a ‘macho man,’ he has deep-rooted feelings of personal inadequacies. Your offender has a maximum of high school education. When he is with children, he feels superior, in control, non-threatened. While your offender may not be from the city where the victim was abducted he certainly has been there many times before (i.e., visiting friends, relatives, employment). He turned towards alcohol and/or drugs to escape from the realities of the crime.”

Even without knowing how things turned out, I would have thought this unhelpful. Who doesn’t feel superior, in control, and non-threatened when among children? In any event, the police arrested Robert Buell only after one of his victims escaped.

At the time, Buell was 42 years old. He had a college degree and was employed by the city of Akron, writing loans for the Planning Department. He was dating an attorney. He had a daughter at Kent State. Those who knew him described a neat, clean, orderly man, almost to the point of obsessive-compulsive disorder. He didn’t exactly fit the FBI’s profile of their child killer.

So that’s the second burn of John Douglas in the book, which you’d think would be two too many for someone with his reputation as a legendary mindhunter. As I’ve said before, there are good reasons why the public has stopped trusting experts.

Though it’s hard to characterize an annual anthology like this as having a particular theme, the fact that they have editors with presumably different interests and points of view does mean that each volume has its own character. In the inaugural collection edited by Nicholas Pileggi I noticed a recurring interest in the theme of bad fathers. In 2007 I found a lot of the stories had to do with a betrayal by individuals in a position of trust. If I had to point to a theme for the 2008 edition I might say it’s community.

Before the advent of the digital age, with its romance scammers and crypto frauds, most crime was local. It matters that the first story here is set in Baltimore, the second takes place in Nicaragua, the third in Pittsburgh, and the fourth on an island just off the coast of New Brunswick. In each of these stories the place plays an active part in the events, as do the later stories dealing with border incidents. But community isn’t just about these sorts of locations. It’s also about places like death row, and the community of prison officials and inmates.

In the early twentieth century there was a literary movement known as Naturalism that saw humanity as basically bound by deterministic laws. One’s fate was a combination of heredity (genetics) and environment. This is something a little different than nature and nurture, the terms most often used in explaining criminality, and the question of whether criminals are born or made. Obviously an emphasis on community puts the focus on the environment, but it’s not an equation that’s being argued for here, or even a strict chain of causation. It’s more that place and community do a lot to define what constitutes criminal behaviour in the first place. Is “snitching” worse than witness intimidation? Is taking a shot at a noisy newcomer who’s wrecking the neighbourhood by running a purported drug house a crime? It depends on the neighbourhood and its community values.

Noted in passing:

Over the years I’ve come back many times to an essay by Tennessee Williams called “The Catastrophe of Success,” which was about the impact the success of The Glass Menagerie had on his life. It seemed to me to be the kind of paradox that isn’t often addressed, either by artists themselves or the people who write about them. The point being that it can actually be harder to follow-up a critical or commercial triumph than to break through in the first place, and that success itself can be a crushing creative burden or otherwise be destructive to the conditions that made the breakthrough possible. As Williams put it:

The sort of life that I had had previous to this popular success was one that required endurance, a life of clawing and scratching along a sheer surface and holding on tight with raw fingers to every inch of rock higher than the one caught hold of before, but it was a good life because it was the sort of life for which the human organism is created.

Success, however, brought not only the comfort of “an effete way of life” but a sense of “spiritual dislocation.” “Security,” Williams concluded, “is a kind of death.”

For Malcolm Lowry life never became that cozy, but after Under the Volcano there would be no second act. And he might have recognized something in what Williams said. “Success,” Lowry wrote to his mother-in-law, “may be the worst possible thing to happen to any serious author.”

Takeaways:

Crime is defined by a community, and though not always restricted by place it at the very least always has a specific cultural context. From the Histories of Herodotus:

Just suppose that someone proposed to the entirety of mankind that a selection of the very best practices be made from the sum of human custom: each group of people, after carefully sifting through the customs of other peoples, would surely choose its own. Everyone believes their own customs to be by far and away the best. From this, it follows that only a madman would think to jeer at such matters. Indeed, there is a huge amount of corroborating evidence to support the conclusion that this attitude to one’s own native customs is universal. Take, for example, this story from the reign of Darius. He called together some Greeks who were present and asked them how much money they would wish to be paid to devour the corpses of their fathers – to which the Greeks replied that no amount of money would suffice for that. Next, Darius summoned some Indians called Callantians, who do eat their parents, and asked them in the presence of the Greeks (who were able to follow what was being said by means of an interpreter) how much money it would take to buy their consent to the cremation of their dead fathers – at which the Callantians cried out in horror and told him that his words were a desecration of silence. Such, then, is how custom operates; and how right Pindar is, it seems to me, when he declares in his poetry that “Custom is the King of all.”

I try and keep my crime local, targetting local businesses and individuals, and keeping it in the community. I’d love to offer more on a bigger stage, but it’s important to maintain firm connections within my own postcode, to be known for what i do, and to find sympathetic victims or fellow criminals.

LikeLike

But now with the World Wide Internetz it’s so easy to globalize. I’ve had scammers from Glazgo target me. You need to get in on the action.

LikeLiked by 1 person

OK, but Alex, you are in danger of being scammed! Your credit cards are at risk! Photpgraph them front and back, and send me the pics; I’ll protect them for you.

LikeLike

Funny, that’s the same thing they were asking me to do . . .

LikeLike

Ahhh, I see the fatal flaw with Darias’s experiment. He didn’t offer the greeks any bbq sauce. They would have devoured their dear old dads if he had done that, I guarantee it!

LikeLike

Alas, all they had was olive oil.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the parent eating bit is a show stopper in this review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not if you add enough bbq sauce! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not invented yet!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s what THEY want you to think. Ancient cave drawings recently come to light show that ancient civilizations were far more advanced than we give them credit for. Including the creation of bbq sauce. It is the force that binds our race together through time and space.

Kind of like the Spice, but better 😉

LikeLike

Ancient aliens brought BBQ sauce to Earth? To eat earthlings? This all sounds a bit diabolical.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Says the man reviewing books about true crime

😉

LikeLike

I’m not reviewing alien cookbooks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you asked yourself the question,

“But Should I Be?”

LikeLike

That’s how they did it in olden days!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very conservational.

LikeLike

We were all green back then.

LikeLiked by 1 person