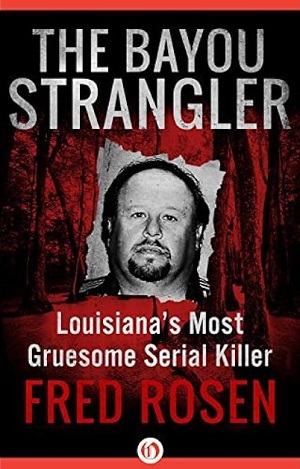

The Bayou Strangler: Louisiana’s Most Gruesome Serial Killer

By Fred Rosen

The crimes:

Between 1997 and 2006 Ronald Joseph Dominique raped and murdered (mostly by strangulation) 23 men and boys in the bayou region of southern Louisiana. In order to avoid the death penalty he pled guilty to eight counts of murder and was sentenced to life in prison.

In his book American Serial Killers: The Epidemic Years 1950 – 2000, Peter Vronsky describes that time frame as a sort of demonic golden age of murderous predators, both in terms of their activity and their fame. Here’s how I summarized the point Vronsky makes in my review:

The numbers are remarkable. In the 1950s there were 72 reported serial killers in the U.S. In the 1960s, 217, in the ‘70s 605, in the ‘80s 768, and in the ‘90s 669. But then a trailing off, with 371 in the 2000s and 117 in the 2010s.

There’s more to the story than just these statistics. Anyone who reads much in this area will know that these same epidemic years (1970-2000) didn’t just produce a greater number of serial killers but all of the names that are still most recognized today: Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, David Berkowitz (Son of Sam), Richard Ramirez (the Night Strangler), Jeffrey Dahmer, and many others known almost exclusively by their nicknames: the Hillside Strangler, the BTK Killer, the Green River Killer et al. But since Dahmer, what killers have caught the public’s imagination and the media’s eye in the same way? Vronsky lists off eighteen of the more prominent, only to say “If you haven’t heard of them, you are not the only one. Some didn’t even have monikers.” I count myself among the ignorant, pulling a blank on all eighteen.

Have serial killers changed? Has the way we cover them changed? Or are we just not as interested as we used to be?

And as for after those eighteen post-Dahmer killers I pulled a blank on, here’s another list from Vronksy:

The few hundred “freshmen” serial killers (as opposed to “epidemic era” Golden Age carryovers) apprehended over the last twenty years are just as anonymous as those arrested in the 1990s following Jeffrey Dahmer. Who has heard of Terry A. Blair, Joseph E. Duncan III, Paul Durousseau, Walter E. Ellis, Ronald Dominique, Sean Vincent Gillis, Lorenzo Jerome Gilyard Jr., Mark Goudreau, William Devin Howell or Darren Deon Vann?

Did you catch the name of Ronald Dominique dropped right in the middle there? Because it’s this anonymity that Fred Rosen begins with as well. “You’d think,” he begins, that “the serial killer who killed more victims than any other serial killer in the United States during the past two decades . . . would have been enough to generate books, movies-of-the-week, films, TV-magazine broadcasts, and podcasts.” But that didn’t happen in the case of Dominique.

Why not? “The sexuality of the killer and his choice of victims got in the way.”

I’m not so sure about this. John Wayne Gacy makes Vronsky’s list of famous killers of the golden age, and of course Jeffrey Dahmer is one of the best-known serial killers in history. Both were gay. I think the thing about Dominique is he just wasn’t very interesting in any way. His crimes were merely brutal and callous, without anything about them to make them stand out. He wasn’t a cannibal or a killer clown but just a short, chubby loser without any friends who lived in a trailer hooked up to his sister’s power, drifting from one dead-end job to another (meter reader, pizza delivery guy, etc.) before finally being arrested in a flophouse. The fact that he was for a time a drag performer who liked to dress up as Patti LaBelle was about the only bit of colour in his drab existence. As Rosen’s references to films and movies-of-the-week suggest, Dominique had no star power. Even his crimes weren’t media sexy, with no signature elements, which left the police able to work in relative peace because the murders weren’t being played up. Indeed, they were barely covered at all.

Invisibility is a super power enjoyed by many serial killers. I don’t mean this in reference to Dominique’s mostly invisible victims, though that was in play here. A lot of serial killers prey on victims who are not immediately missed when they disappear. I think Rosen is probably right when he says that “Dead black men, gay or not, doesn’t sell on the news,” and that “If Dominique had only chosen different victims, whose lives were more valued by society, then the state might have acted earlier.” But that’s not what I mean by invisibility.

What I mean is that Dominique was himself someone who nobody cared about. When finally arrested few people believed him capable of killing so many people, and this was not a moral judgment. He was just so unprepossessing. This in turn allowed him to work quietly for nearly a decade without anyone seeming to notice. He didn’t seek notoriety by writing letters to the police or to newspapers, but at the same time he did little to conceal his tracks. Even his use of a condom when raping his victims was probably attributable to his fear of infection, as he was a pronounced hypochondriac, rather than a desire not to leave any DNA evidence.

In such cases I’m reminded of the scene in The Collector where the kidnapped Miranda says to her captor Freddie “Look, people must be searching for me. All of England must be searching for me. Sooner or later, they’re going to find me.” He coolly replies: “Never. Because, you see . . . they’re looking for you, alright, but nobody’s looking for me.” Like Dominique, he was invisible.

And so “the worst serial killer of the new millennium” is someone even true-crime buffs may know nothing about. Rosen tries to build him up, saying things like “If Dominique were a nineteenth-century gunslinger, he would have twenty-three notches on his gun,” but it just doesn’t work. Dominique wasn’t a gunslinger, but a violent, lonely, and bitter gay man who may have been motivated to kill people as much by boredom as anything else.

I can’t say I really liked the book. I found it disappointing. Perhaps a lot of this was because I had been looking forward to it, seeing as I’d never heard of Dominique before this. But I subsequently felt like I got more information out of a 40-minute documentary I watched on his murderous career than I did from Rosen. I appreciated the book clocking in at under 200 pages, but one effect of being so quick was that the events started to blur and it got hard to keep track of Dominique’s location and employment at various times. The photo section at the back was inadequate and I felt like maps of the region would have been really helpful. There were also a number of little flourishes I didn’t care for, like the aforementioned references to the notches on a gunslinger’s gun. Another moment came when an acquaintance of one of the victims describes him as being “a little off mentally” and so incapable of selling dope. “Not that you had to be smart to be a drug dealer,” Rosen can’t help adding. I thought this was being flip. I think that to be a successful drug dealer (meaning at a minimum one who is capable of making a bit of money and staying out of jail) you probably do need to be pretty smart.

Noted in passing:

“Louisiana’s Most Gruesome Serial Killer”? This struck me as a bit of cover-bait sensationalism on at least two counts. First: what was the competition? While I’m no great student of serial killers, I had heard of the infamous Axeman of New Orleans. Wasn’t he more gruesome? He did hack people to death with an axe, after all. Second: is “gruesome” the right word? The dictionary definition is “inspiring horror or repulsion,” but I think every serial killer does that. The actual etymology goes back to a Germanic word for “shiver.” Personally, I’ve always linked it to gore. But Dominique didn’t butcher his victims. In fact, he seems to have been a tidy killer, leaving very little in the way of physical evidence behind. Rosen tells us that during his taped confession, “the gruesomeness of [Dominique’s] crimes made even seasoned pros cringe,” but I don’t know what evidence there was for that. Dominique raped his victims and then strangled them, disposing of their bodies later by throwing them on the side of the road. Which, while brutal behaviour, isn’t what I’d characterize as gruesome.

Sticking with preliminaries, the epigraph comes from Ernest Hemingway: “There is no hunting like the hunting of man, and those who have hunted armed men long enough and liked it, never care for anything else thereafter.” This is a blustering bit of machismo taken from a column Hemingway wrote for Esquire magazine about fishing that later turned into the core of The Old Man and the Sea. I don’t know what it has to do with Dominique’s hunting humans. He certainly didn’t hunt armed men, the most dangerous game, but rather, like most serial killers, sought out the weakest and most vulnerable members of society.

In my notes on Monster I was impressed at the number of gay bars in big cities. Apparently there were 8 in Milwaukee at the time, and over 70 in Chicago. According to Rosen, in the 1990s there were “exactly two gay bars” in the town of Houma, Louisiana. This surprised me, as the population of Houma was only around 30,000 at the time, and it doesn’t seem like it was a very “metro” community. I live in a university town of just over 140,000 and when I checked online we didn’t have any gay bars, but only LGBTQ-themed nights at a couple of establishments.

The attempt to take fingerprints from one of the victim’s skin is something that one of the detectives learned from watching CSI. “Somewhere,” Rosen writes, “CSI star and producer William L. Peterson must be smiling. His TV show was helping to solve a real-life serial-killer case!” That’s a feel-good moment, I guess, but it made me wonder why a homicide detective hadn’t picked up on this from any of his training.

Takeaways:

If a stranger asks if he can tie you up, the correct answer is always No.

Serial killers just aren’t what they used to be, the standard has fallen alongside the decline fo the English murder. How can we attract young people, so busy with social media, back to more wholesome ways to achieve fame and noteriety like brutally murdering other people? Financial incentives? More teaching about the benefits of serial killing in schools? What happens if the numbers dwindle down to nothng, what will you read about and blog about on Sundays then?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gentlemen jewel thieves. Frauds and scammers. I’ll find something to talk about.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The old days when leaving a monogrammed silk glove at the scene of the crime was essential. Where have these standards gone?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Social media killed them. Instead of trying to commit the perfect crime we have kids who want to take selfies with a diamond necklace or a well-arranged corpse. You can’t create a criminal masterpiece just for the likes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If a stranger asks if they can tie you up, your first response should actually be to pull out your gun and tell them to lie on the ground until the cops arrive. You know you’ve got a sicko on your hands if someone asks you that.

LikeLike

Well, if you have a gun on you. Which I’m assuming you always do . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

NH has constitutional carry 😉

LikeLike

So you can carry a concealed copy of the Constitution?

LikeLiked by 1 person

At all times. So when the fuzz try to camp out in my condo, I wave the Constitution at them and tell them “no sirreee”…..

LikeLike

That’s exactly how I thought it worked. You know your rights.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Plus, if I ever travel to Europe, I can kill people willy nilly, like Jason Bourne and then wave the Constitution at them and they have to let me go.

LikeLike

Sort of like diplomatic immunity, but with extreme prejudice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I mean, if Bourne can kill a guy with a magazine, surely I can kill someone with our Hallowed and Sacred Constitution?

LikeLike

I think any European would consider it to be an honour.

LikeLiked by 2 people

If they don’t, I’ll make them eat a double cheeseburger instead….

LikeLiked by 1 person

With bacon, it should do the job almost as quickly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, a double bacon cheeseburger. Yep, that’s American as you can get. And just as deadly…

LikeLike

I’m European and I wouldn’t be keen to be killed with a copy of the constitution, concealed or otherwise…

LikeLike

You say that now, but have you really engaged with its sonorous prose and lofty ideals?

LikeLike

with you on this point.

LikeLike

He looks ugly and sounds boring, of course they’re not gonna do a movie of him!

LikeLike

I think that pretty much closes the door on his film career.

LikeLiked by 1 person