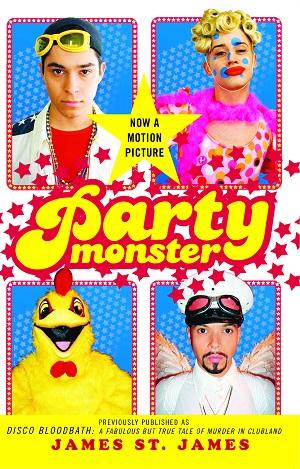

Party Monster

By James St. James

The crime:

The Club Kids were a flamboyant bunch of mainly 20-something, mainly gay men who made a big splash as the media darlings of New York City’s club scene in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As their moment in the spotlight drew to a close and their drug habits got harder to maintain one of the more prominent of the Kids, Michael Alig, along with a friend named Freeze (Robert Riggs), killed fellow Club Kid Andre “Angel” Melendez during an argument over a drug debt. Melendez’s body was then dismembered and thrown in the Hudson River. This was in March 1996. Alig and Riggs would both go to jail, with Alig being released in 2014 and dying in 2020 from a drug overdose.

A real change-up from the last book I covered! In my notes on Kate Summerscale’s The Wicked Boy I talked about how impressed I was by Robert Coombes, and how he’d managed to rebuild his life after killing his mother and being incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital for 17 years. From very humble beginnings (finished school and working in the East End dockyards by the age of 13) he’d gone on to become a decorated soldier in the First World War, an accomplished musician, and a successful farmer, among other things.

Compare and contrast the lives of the Club Kids, many of whom came from reasonably well-off if not privileged backgrounds and equipped with decent educations. They then came to New York and . . . partied. Played dress up. Took a lot of drugs (ketamine, heroin, cocaine). Were terrified of getting old, which for St. James meant turning 30. No, these weren’t Victorian kids who had to grow up fast but artificial “kids” who never wanted to grow up at all.

One has to wonder what any of them were actually good at. Certainly not killing people. The messy work Freeze and Alig made of offing Melendez was cruel in its sheer incompetence. Making a scene? I guess Alig’s semi-official job title was party promoter, and that could be seen as work, of a sort. Meaning it had economic value, at least until it didn’t. But if you’re like me you’ll probably read Party Monster (originally titled Disco Bloodbath and re-released as Party Monster when a movie came out) wondering what any of the Club Kids did to make money. Based on my own limited acquaintance with similar people in Toronto around the same time, I think that prostitution was a big part of it, but James St. James (himself one of the Club Kids) doesn’t mention this, and he’s generally pretty open about the dark side of the Club Kid lifestyle.

I don’t want to play the old man shaking his head at kids today, or make this comparison to Coombes in order to put forward some argument about the decline of Western civilization. But I did find the shift from Coombes to Alig not only jarring, but one that says something – not so much about moral decadence as about the loss of what might be described as general competence. It’s not that if you dropped the Club Kids naked into the jungle they wouldn’t be able to survive. They weren’t even getting by in NYC without the support of people like “the Patron Saint of Downtown Superstars, Peter Gatien,” who took care of “all those little things like bills and rent and food and outfits.”

There are two further points this raises.

First, not having to worry about “all those little things” leads to the terrible condition that Alig fell into where reality “could simply be dismissed.” He began to feel that “the OUTSIDE WORLD NEED NEVER TOUCH HIM,” from whence arose “a perfectly understandable onslaught of delusions of grandeur.” This actually made me think of Kurtz kicking aside all restraints in Heart of Darkness. And we know what happened to him.

The second point this moral squalor and coked-up narcissism leads to is the question of just how much we can care about any of the Club Kids and their dismal fates. Personally, I didn’t like them at all. Their behaviour was vicious and self-destructive and I didn’t find anything about them to be endearing or cute. Alig in particular seems to have been a thoroughly nasty piece of work, and at one point St. James himself writes off the scene as populated by “nasty sons-of-bitches, the whole lot of them.” But leaving my personal feelings aside, this lack of empathy or sympathy is not something I’m bringing to the book but a point St. James frequently addresses himself.

He makes it clear, for example, that he absolutely hated (his emphasis) Melendez, and that he didn’t think his murder was any great loss. He didn’t care. Indeed “nobody cared about him” among the clubbers, except insofar as he was their dealer. The police didn’t care about him: “Not one lick.” His (real) family cared, but St. James doesn’t have any time for them. And so he poses us a question (the use of block caps, bold, and italics are all in the original; it’s just the way St. James writes):

If one day, Mother Teresa was out weed whacking and accidentally chopped off Hitler’s head – WOULD THAT NECESSARILY BE A BAD THING?

I mean . . . if a person commits a crime, and no one cares – can we all just adjust our lip liner?

Look, I’m just being honest here. I think that the whole point of my story is that nobody ever implicated Dorothy in the double witch homicides of Oz because, well . . . you know . . . She’s Judy Garland, for God’s sakes, and Louis B. Mayer forced her into a life of drugs at such a young age, poor thing . . .

This is protesting, or pleading, a bit too much. Angel was Hitler? Alig was . . . Judy Garland, “forced . . . into a life of drugs”? Later, St. James will present this key question to us as “the old Dostoyevskian Conundrum: if you kill an unlovable cretin, is the crime still as heinous?”

To give St. James his due, this is the kind of question that I think a lot of true crime forces us to consider. There are victims who we don’t extend a lot of sympathy towards, either because they are seen as having contributed to their own destruction or because they’re just horrible people. That said, it’s a point that, when you step a little further back to look at the whole Club Kids phenomenon, takes in everyone. As a reader it’s easy to look on with horrid fascination at these circus/freak show proceedings, in part because grabbing your attention was what being a Club Kid was all about, and in part because this is such a compulsively readable book. I enjoyed every page of it, without caring much about any of the people in it at all.

Noted in passing:

I was reading a movie tie-in edition that had the obligatory “Now a Motion Picture” bubble on it. But not a major motion picture, as is usual (for previous thoughts on this, see my post on The House of Gucci). I don’t think anyone had any illusions on the score of this being a “major” film. Though calling it a motion picture is itself a form of high praise. Who says “motion picture” anyway? Who even writes it? I think this is one of the only places you can still see it being used.

Takeaways:

Every party has an end, so you should make arrangements ahead of time for your ride home.

BANG BANG BANG

WAAAAAAAKE UP!!!!!!!!!

Oh, right, this post is from today. Errr, carry on then…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I got up at midnight and was thinking of banging some pots over at your site, but I decided to go back to bed and let you sleep in.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Time change, baby! I got up an hour “earlier” 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Think of all the things you can do in that extra hour!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Drink an extra can of energy? Sounds good!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Drinking that stuff at breakfast will kill you. I think that’s a health warning right on the label.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Living life will kill you too. Every single person I know who has died made the mistake of getting born and then living their life.

I’m willing to take my chances 😉

LikeLike

Murder is murder. But murder is premeditated, so his example of Mother Teresa and Hitler is so off course that it shows what he is really after; an excuse to say “It’s not my fault.” Which fits in with his whole lifestyle.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m going to go waaaaaaaay out on a limb here and say that you’d hate this book and all the people in it!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know I would hate the people in it. And since the author was one of them (I did get that right, correct?), and given the little bit you quoted, I suspect I would hate the book too. With a mighty passion of disgust…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah the author was one of the Club Kids. As for his writing style, he’s no Jane Austen . . .

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m surprised he was able to string together 5 words into a sentence. Probably had a ghost writer doing all the heavy lifting…

LikeLiked by 1 person

He might have dictated it. As the examples I quote show, he writes like I imagine he talks.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I don’t think I would like it or the people either, the author sounds a right plank.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not sure if he ever grew up. From recent photos I think he just got older.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw the movie of this. A lot of stupid young people who seem to think that getting mashed is an achievement. And then took it too far. A bad scene.

LikeLike

I was curious about the movie but couldn’t find it online. I watched the trailer and it looked kind of bad. I sort of assumed it was bad because apart from this book I would have never heard of it.

LikeLike