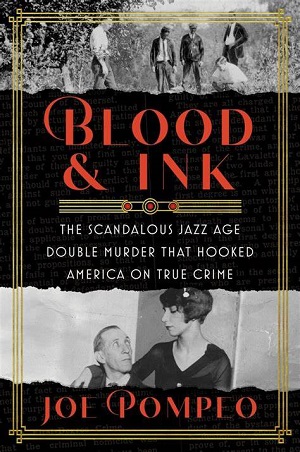

Blood & Ink: The Scandalous Jazz Age Double Murder that Hooked America on True Crime

By Joe Pompeo

The crime:

Edward Wheeler Hall, a priest, and Eleanor Mills, a choir singer, were found dead on the morning of September 16, 1922, their bodies arranged together under a crabapple tree. Both Hall and Mills were married, but not to each other. The prime suspects were Hall’s wife Frances and her siblings, but after years of investigation and the circus of a huge trial they were found not guilty and the case remains unsolved.

The title tips you off that Joe Pompeo is going to come at the story from the angle of its media coverage, which I think is justified given how big a deal the Hall-Mills case was at the time. I don’t think it’s as well known today, though among true-crime connoisseurs it remains a favourite: a fun case to dig into, both for being unsolved and for the colorful cast of characters.

It’s a bit misleading though to say the case hooked America on true crime, and in his conclusion Pompeo admits that the press coverage only “arguably laid the groundwork for the genre as we know it.” I don’t think he’s as interested in the genre of true crime anyway as he is in the rise of tabloid journalism. The two were connected, though not the same thing. Joe Patterson, one of the first tabloid impresarios, had it down to a formula: the subjects that most interested readers were “(1) Love or Sex, (2) Money, (3) Murder.” He also believed that readers were “especially interested in any situation which involved all three.” The Hall-Mills case hit the trifecta. As one reporter covering the trial put it, “It has a combination of every element that makes a murder case great.”

So the story of the case and how it was covered go together, especially when the tabloids themselves, mainly in the person of New York Daily Mirror editor Phil Payne, became the driving force in the investigation. And like the best cultural history it reflects a critical light back on our own media ecosystem. When the Daily Mirror launched it promised readers “90 percent entertainment, 10 percent information.” Clearly the days of infotainment were upon us. As William Randolph Hearst (publisher of the Mirror) understood, “People will buy any paper which seems to express their feelings in addition to printing the facts.” So the foundations for today’s media silos were being poured as well.

Other points of reference are even more intriguing. The Evening Graphic made use of an innovation called the “composograph” that apparently worked by superimposing the faces of story subjects on body doubles, thus creating deep fakes a century ahead of schedule. And the publisher of the Evening Graphic was also a health and fitness nut who wanted to use the paper to “crusade for health! For physical fitness! And against medical ignorance!” What this meant, among other things, was a competition to find ideal human specimens (“Apollos and Dianas”) who would be “perfect mates for a new human race, free of inhibitions, and free of the contamination of the smallpox vaccine!” A eugenicist and anti-vaxxer then.

This is all interesting stuff, but in the drive to get to the totemic 280 pages there’s still a fair bit of filler. I was uninterested in the details of Payne’s life and death, or the story of cub woman reporter Julia Harpman, as inspiring a figure as she may have been. Payne in particular seems to have been more than a bit of a jerk, and it’s hard to tell if he really believed any of the trash news he was trying so hard to manufacture out of nothing, or if he cared about any of the people he might have been hurting along the way.

As for the crime itself, it’s continued to cast its spell over armchair sleuths for generations. There’s the sex not only at the heart of the story but also creeping around the edges. The bodies were discovered just off the local lover’s lane by Ray Schneider and Pearl Bahmer, a pair who authorities discovered were up to no good. This grand jury confrontation between the lead detective on the case and the young man involved must have been shocking stuff:

“Did you go up there,” Mott demanded, “knowing that [Pearl] was having her period, for the express purpose of lying down on your back, as you did, and [having] her do the vile thing she did to you? Wasn’t that why you were there?”

“No, sir,” Ray lied. “It was not.”

In addition to the sex (I’m still going off Patterson’s trinity here) there was the money. Or class. Hall represented money, even if only by marrying into it. Mills came from a less privileged background. But the split was also there in the arrest of a young man named Clifford Hayes, who was soon cleared of any involvement. Harpman drew the storyline in clear terms:

The law says certain things about equality of rich and poor. But the law speaks with its tongue in its cheek. The law says the rich Mrs. Frances Stevens Hall . . . deserves no more consideration than Clifford Hayes, the young man who was thrown into prison on the unsupported accusation of an irresponsible character. But the eyes of reality see an impassable gulf – a chasm cleft by the sinews of wealth – between the preacher’s widow and the swarthy young sandwich cook, who worked, when he did work, in a side-street lunch cart.

Later, when Frances herself was arrested, the conflict was drawn between “the masses and the classes.” Which was a divide that everyone in 1920s American could relate to. It’s interesting that in our own time, where the level of inequality has managed to regress to the level of those years, the language of class has mostly been retired. As cited by Paul Fussell in his excellent book on the subject, class is America’s “forbidden subject.” We’re still drawn to stories of rich people behaving badly, but there’s no sense of an “us against them” anymore.

Finally there’s the murder, and “the million dollar question” that remains of Whodunnit?

My own take is close to that of Bill James, as laid out in his book Popular Crime (in which there was also a lot I did not agree with). Given the nature of the crime – basically the execution of an adulterous pair who were not robbed – I think it very likely that the killer(s) knew the victims very well. Indeed, that they knew where and when they were meeting the night they were killed. That basically leaves two groups of suspects: Frances and her brothers, or James Mills (Eleanor’s husband). Pompeo sees Frances as “the most obvious” solution to the mystery, reasoning that “there was too much smoke around Frances and her brothers for there not to have been any fire.” Unfortunately, a lot of the smoke was proven to be just that. Meanwhile, I agree with James in seeing the disproportionate violence directed at Eleanor as significant. Edward Hall was shot once while Eleanor was shot three times in the head and had her throat slit. This suggest a special order of anger. It’s possible that Frances or one of her brothers might have felt this same level of rage, but it seems to me that James Mills was more likely to have gone over the edge.

Noted in passing:

There’s a wonderful moment in the trial for all lovers of language and anyone interested in how the meaning and usage of words changes. The prosecutor Simpson is questioning Frances:

“When you got up,” Simpson said, referring to the morning after Edward’s disappearance, “you telephoned police headquarters?”

“I did.”

“You were looking for information about your husband?”

“Yes.”

“You thought you would get it from the police?”

“I thought I would hear of any accidents.”

“Accident was in your mind?”

“Yes.”

“But you said to the police, ‘Have there been any casualties?’”

“Doesn’t that mean accident?”

“Weren’t you looking to see if the dead bodies had been found?” Simpson pressed. “If you used the word ‘casualties,’ and you had accidents in your mind, why did you use the word ‘casualties’?”

“It means accidents,” Frances replied. “It is the same thing.”

“It also means death, doesn’t it?”

“I do not know that it does.”

“So, with your understanding of the meaning of the word, you telephoned police headquarters, you did not give your name, and you asked for casualties? You thought, you say, maybe there had been an accident, maybe your husband had been hurt in an automobile accident?”

“Yes.”

Today I think most of us take “casualties” as referring to lives lost either in battle or in natural disasters (though non-fatal injuries in both cases are still considered casualties). But Frances is correct, in an upper-class sort of way, that it could refer to any loss through accident or misfortune, to life or property and possessions. In the insurance industry it still has this broader meaning, though it too has evolved and mainly refers today to liability insurance. I love how Frances and the prosecutor can’t understand the words they’re using, even when they are the same words.

Takeaways:

Pompeo uses the term “trial of the century” as a chapter heading, and it may be that in 1926 Hall-Mills deserved that appellation. However, I don’t recall any of the journalists covering it using those words. In any event, in 1935 the Lindbergh kidnapping trial effectively supplanted it and would go on to hold that title at least for another seventy years. The only challenger I can think of would be the O. J. Simpson trial in 1995. But as F. Lee Bailey said in the aftermath of the Simpson circus, “trial of the century” is just “a kind of hype. . . . It’s a way of saying, ‘This is really fabulous. It’s really sensational.’ But it doesn’t really mean anything.”

Sounds like a ‘hell hath no fury….’ situation!

LikeLiked by 1 person

If it was the wife, she was a cool customer as well as being mad as hell. But then being a member of the upper crust she had breeding to see her through.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Will you be running a ‘competition to find ideal human specimens’ on your blog? Where can I sign up?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t need to go looking for those. Already got one.

LikeLike

Where do you keep it?

LikeLike

The mirror in the bathroom.

LikeLike