Vanished: Cold-Blooded Murder in Steeltown

By Jon Wells

The crime:

Acting on a tip that came in on Easter weekend 1999, police found a garbage bag stuffed with body parts on steelworker Sam Pirrera’s front porch. The remains were later identified as belonging to Maggie Karer, a Hamilton sex worker. As police investigated the case it became clear that Pirrera might also have had something to do with the disappearance of his first wife, Beverly Davidson, eight years earlier. Charged with the murder of both women, Pirrera died of a drug overdose, almost certainly suicide, just before his court date.

The book:

The book:

While grisly, the crimes here were nothing out of the ordinary for tales of domestic abuse escalating to murder. Pirrera was a violent cocaine addict who spiraled out of control. In fact, the presumed murder of Beverly took place in a manner that I have alerted people to before on several occasions and I can only repeat my earlier takeaways: If the relationship is over, it’s over. You don’t arrange to meet up with your ex for a talk about whatever outstanding issues you may have, especially if there’s not going to be anyone else around. This is part of the value of reading true crime; you can learn something from it.

I suppose killers could learn some lessons as well. One of the chief among these is the disposal problem. Especially given the advances made in forensics, a killer has to be able to make all of the evidence disappear. And I don’t mean just tossing body parts in the garbage, or trying to flush them down the toilet (the latter method being how both Dennis Nilsen and Joachim Kroll were caught when the remains backed up the plumbing). Not even the wood chipper from Fargo is going to do the trick, since that will leave blood splattered all over the inside of the machine. It’s hard to make the evidence of a body disappear entirely. When Dellen Millard used a portable livestock incinerator (known as “The Eliminator”) to get rid of the remains of Tim Bosma there were still some of his bone fragments found in it.

No, if you’re going down this road you have to be able to make a victim literally disappear. When looking for evidence of Pirrera’s having killed his first wife, Beverly, police scoured the house they had lived in together eight years previously, and which had long been occupied by another family, scanning the basement and bathrooms for microscopic traces of blood. They didn’t find anything, but the very idea that they would undertake such a search gives you some idea of what is possible.

Unfortunately for the police, Pirrera is presumed to have disposed of the body of his first wife in a way that was practically foolproof. As noted, he was a steelworker, employed (fitfully, as his issues with cocaine addiction ramped up) at the local Stelco works. (To explain the title to those not familiar with the place: Hamilton, where the crimes took place, is known as “Steeltown” because of its history with that industry) The theory the police had was that he cut the body up and then threw the pieces into a vat of molten steel. That’s making a body disappear. It reminded me of how Robert “Willie” Pickton, the serial killer/pig farmer in British Columbia who killed nearly 50 women, may have got rid of the bodies of his victims by taking them to a rendering plant, feeding them to the pigs, or grinding them up and mixing them with pork he sold to the public. I think the rendering plant theory in particular almost as effective as the vat of molten steel. In any event, what caught Pickton out in terms of physical evidence was the fact that he held on to some personal items belonging to his victims. I think the only body parts they located were a few skulls.

This was a brutal case, with the brutality mostly being the consequence of Pirrera’s drug abuse. That sort of thing rarely ends well, though it doesn’t often blow up as badly as it did here. It’s a tribute to Wells’s ability to tell a story though that he turns these events into such an effective work of true crime reporting. I think two things helped. First, it isn’t a timely book. Karer’s murder took place nearly ten years before Wells wrote about it, which allows for a bit more perspective from all the people involved. Second, the specially commissioned photos by Gary Yokoyama add a lot. I like to complain about true crime books where the photo sections consist of poorly reproduced pictures that sometimes have only a tenuous connection to the story, so it’s nice to be able to give credit to a book that made an extra effort in this regard.

Noted in passing:

The house where Pirrera killed Karer turned into a local site of interest, so that people would even come and knock on the door asking the new owners if they could look at the basement (which had subsequently been refurbished). It got so bad that the owners “asked, and received, city permission to change the number 12 on the façade to a different number for a $130 fee.” Which is nice, but I didn’t understand how that would work. Legally the address would have to be the same for emergency services, so I guess this just meant they put a different number on the door or over the garage. But who would this fool? Anyone motivated enough could just count the numbers of the houses on the street and would notice a jump from 10 to 14, while everyone else would just get confused. How would deliveries work? This seems really strange to me.

Another point I wanted to flag has to do with the book’s preliminary material, being a couple of pages of blurbs of “Praise for Jon Wells.” One of these blurbs comes courtesy of Alex Good in a review of the book Poison that I did for The Record back in 2009. Two things struck me about this. One good: all too often these blurbs are just quoted and then the name of the publication given. It’s nice that I got credited by name. Thank you! Reviews don’t write themselves, you know. One bad: I looked and couldn’t find my review of Poison. I remember reading and reviewing it but I guess I never posted the review at Good Reports and it wasn’t anywhere else I checked. If I want to retrieve it now I’m probably going to have to fire up an old computer and see if it’s somewhere on the hard drive. I sure don’t have a print copy. Nothing lasts forever, people!

Takeaways:

Cocaine is a hell of a drug. Stay away from the stuff.

True Crime Files

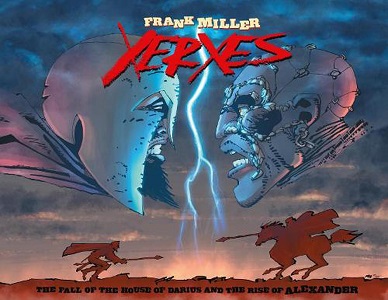

I guess you could call this a sequel to 300, but it came out in 2018, which was 20 years later, and doesn’t have much to do with the events of Thermopylae, which it skips in its race through over 150 years of Persian history. There’s also no real connection to the movie 300: Rise of an Empire, which actually had come out four years earlier.

I guess you could call this a sequel to 300, but it came out in 2018, which was 20 years later, and doesn’t have much to do with the events of Thermopylae, which it skips in its race through over 150 years of Persian history. There’s also no real connection to the movie 300: Rise of an Empire, which actually had come out four years earlier.