This was a neat little idea. There were a dozen mini-puzzles in the box, each an irregular shaped picture of a dog making a funny face. (They call them “selfies” even though I don’t think the dogs were taking the pics.) Each mini-puzzle has a different colour of backing, so you can sort them out before you get started, or just try to do them with all the pieces jumbled together.

The Immortal Hulk Volume 2: The Green Door

The Immortal Hulk Volume 2: The Green Door

On the plus side, there were some crazy fights here, as the Hulk’s new-found immortality is pushed to the limit and beyond. He’s approaching god-level power and is strong enough take on all of the assembled Avengers. Even if you blow him up with a space laser and then dissect him with adamantium blades his parts keep reassembling, which just leads to another big green can of whoop-ass being opened up. The effects can be grotesque in a truly novel way, and his various pieces coming back together to take out one of his tormentors is well worth the double-page spread. Meanwhile, Skinny Hulk, with his gamma power being drained by Absorbing Man is also freaky, and what happens to poor Absorbing Man is off the charts.

On the plus side, there were some crazy fights here, as the Hulk’s new-found immortality is pushed to the limit and beyond. He’s approaching god-level power and is strong enough take on all of the assembled Avengers. Even if you blow him up with a space laser and then dissect him with adamantium blades his parts keep reassembling, which just leads to another big green can of whoop-ass being opened up. The effects can be grotesque in a truly novel way, and his various pieces coming back together to take out one of his tormentors is well worth the double-page spread. Meanwhile, Skinny Hulk, with his gamma power being drained by Absorbing Man is also freaky, and what happens to poor Absorbing Man is off the charts.

In the negative column . . . just what the hell is going on? The Hulkster is possessed by both a literal and metaphorical demon. The latter being the spirit of his abusive father, who still shows up in visions, and the former being I’m not sure what. Maybe an actual emissary from hell, which is where we end up in the end after going through the eponymous green door (which is, sadly, not an homage to one of the signal films of porn chic).

In sum, this is a really weird take on the Hulk mythos – maybe the weirdest yet, which is saying something since it has gone in a lot of strange directions. I have a hunch that writer Al Ewing was trying to do too much. Even the issue epigraphs rarely seemed on point. That said, I enjoyed this volume a lot more than the first, even if it is a dog’s breakfast of crazy. I still don’t know if there’s anywhere it’s going that’s worth getting to, but the trip is turning into a lot of fun.

TCF: The Infernal Machine

The Infernal Machine: A True Story of Dynamite, Terror, and the Rise of the Modern Detective

By Steven Johnson

The crimes:

With Alfred Nobel’s invention of dynamite in 1867, criminals and revolutionaries were handed a new weapon in their war on the ruling classes and peace, order, and good government more generally. To fight against a spate of bombings, law enforcement had to up their game and develop the kinds of practices we now associate with modern policing.

If that summary of what The Infernal Machine is about seems kind of broad, don’t blame me. Steven Johnson specializes in these sorts of popular history grab-bags, and the elements are even more random than usual here. Just for starters I had to shake my head at the subtitle calling this “a true story” – not because any of it is fiction but because there is no story in evidence. The narrative, to give it a fuzzier label, takes us basically from the assassination of Alexander II to the Palmer Raids, with various bombings in-between. Are there threads connecting all of this? Sure. But all too often they struck me as coincidental. I mean, if you stand back far enough, tilt your head, and squint, then I guess everything is connected to everything else on some level. But not really.

I’ll stick to talking about the two main narrative axes that Johnson travels along. The first is political or thematic:

This book . . . is the story of two ideas, ideas that first took root in Europe before arriving on American soil at the end of the nineteenth century, where they locked into an existential struggle that lasted three decades. One idea was the radical vision of a society with no rules – and a new tactic of dynamite-driven terrorism deployed to advance that vision. The other idea – crime fighting as information science – took longer to take shape, and for a good stretch of the early twentieth century, it seemed like it was losing its struggle against the anarchists. But it won out in the end. How did that happen? And could the story have played out differently?

Later, Johnson expresses the terms of this “existential struggle” in slightly different terms, seeing “two rival ideologies” in conflict: “the dream of a stateless society, radically egalitarian, free of the oppressive institutions that had come to define the industrial and imperial age” vs. “the surveillance state, where individual identity is measured, recorded, and archived by vast and often invisible institutions, using the latest science and technology to contain potential subversion.”

This is interesting, but was there really that strong a connection between these two ideas or ideologies? Anarchism never took political root anywhere, but was that because it lost an existential struggle with scientific crime fighting? The surveillance state and modern policing are now ubiquitous facts of life, but did that have anything to do with these early battles against bomb throwers?

I think both developments were, if not inevitable, then at least very likely to have taken place without any engagement with the other. Anarchism suffered the fate of a lot of socialist movements with the outbreak of the First World War, while crime fighting was being driven as much by the advance of technology and the response to other threats like organized crime as it was by dealing with political enemies. And then of course there is the difficulty of defining terms. What is, or was, anarchism anyway? A libertarian movement? A call for class warfare? Were the anarchists who practiced “propaganda of the deed” typical of anarchist thought, or outliers? Is it fair to say that all that survives of the anarchist movement today is terrorist bombings like the 9/11 attacks (“the general tactics of terrorism remain anarchism’s most enduring legacy”)? That seems tenuous to me. Terrorism was a tool used by different ideologies, and it predates the invention of dynamite.

The second narrative axis is built around telling the life stories of a pair of prominent anarchists: Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. As a biographical sketch of the two what you get here is fine, but again the connection to “infernal machines” (that is, explosive devices) and modern policing isn’t that strong. They were both anarchists, of a sort. Maybe Berkman was in cahoots with a cell of bomb makers at some point. Goldman probably wasn’t. The police kept thick files on both, though they were prominent public figures and didn’t keep any secrets when it came to their radical beliefs. So again: is there a connection? Yes, but not a strong one. Neither story really depends on the other.

The critics on the back cover rave: “Johnson is a polymath. . . . [It’s] exhilarating to follow his unpredictable trains of thought” (Los Angeles Times); “Johnson’s erudition can be quite gobsmacking” (New York Times Book Review). I think my gob may be harder to smack. To me, The Infernal Machine just seemed like a whole lot of everything and not much of anything in particular. The effect was sort of like reading a bunch of linked Wikipedia articles. Did Johnson really need to kick off a chapter on the Ludlow Massacre with an account of how coal deposits were formed in the Cretaceous period? That’s not erudition, it’s just cheap display of superficial learning.

There are a few perceptive moments. I liked it when the following comparison was drawn between then and now.

Berkman and Goldman were living in a world where one side of the spectrum thought it was appropriate to execute people who objected to a seventy-two-hour week of life-threatening work – while the other side of the spectrum thought that we should abandon both governments and corporations and reinvent society along the lines of Swiss watchmaking collectives. Those were the distant poles of the debate. What we would now call the Overton window – the space of potentially valid political beliefs – was far wider than anything in American politics today.

That’s well observed, and it’s a point that’s expanded on after a description of the public memorial service held for a group of anarchists who had blown themselves up while constructing a bomb meant to avenge Ludlow:

More than a century later, it is not hard to imagine a small band of disaffected New York City residents – in our present moment – spinning themselves into some kind of cyclone of hate and building a dirty bomb or a bioweapon in their basement. What is harder to imagine is five thousand people showing up in Union Square to mourn their deaths as martyrs to a greater cause. We still have people willing to kill for political ends in countries like the United States, though far fewer of them than there were back in 1914. But when those beliefs materialize into actual dead bodies, you don’t conventionally see a great outpouring of public support for those violent acts. There were no rallies for the Unabomber.

This is something work keeping in mind when thinking of how we live in an age of extremes. I still think it’s fair to consider various schools of political thought today as extreme, but they’re extreme in different ways. One of the things that has changed the most is the level of sheer crazy we’ve grown accustomed to.

Noted in passing:

Johnson uses the word “attentat” over a dozen times in this book. It wasn’t familiar to me, though it’s the same word (same meaning, same spelling) in both French and German as in English. The basic meaning is of a violent criminal act, or assassination. It also has a legal meaning in English, but that is considered obsolete. In fact, I found several sources online that give its use as meaning an attack or assassination as obsolete as well. So I can’t blame myself for being surprised to see it. But it’s properly employed, as it correctly describes the bombings and attempted assassinations that are a big part of Johnson’s subject matter, and was used by Goldman herself, though she capitalized it. I suspect reading Goldman is where Johnson might have picked it up. So I did learn something here, though it’s not a word I’m likely to ever use myself.

Takeaways:

There’s no invention or technical advance that can’t be made to serve wicked ends. And given time, almost any invention will end up being so used.

Alien: Bloodlines

Alien: Bloodlines

In my notes on Aliens: The Original Years I said how much I loved the writing. The way that Mark Verheiden took the story in so many interesting new directions put what happened to the film franchise after James Cameron’s Aliens to shame.

In my notes on Aliens: The Original Years I said how much I loved the writing. The way that Mark Verheiden took the story in so many interesting new directions put what happened to the film franchise after James Cameron’s Aliens to shame.

I don’t think what writer Phillip Kennedy Johnson does in this six-issue story arc is on quite the same level as Verheiden’s work, but it’s very good. A tough-as-nails security chief named Gabriel Cruz has to go back to a space station orbiting Earth when his son joins up with an activist group that wants to throw a monkey wrench into what the Weyland-Yutani Corporation is doing up there. Unfortunately, what they’re doing up there is breeding a bunch of Xenomorphs, so of course things get out of hand. It seems that despite all the time spent studying them we’ve never learned how to handle these critters.

Throw in some Bishop-model cyborgs that all look like Lance Henriksen, a super “Alpha” Xenomorph and a mysterious dark queen of the hive, and a strange subplot that has the Xenomorphs forming a psychic bond with Gabriel because he’d survived incubating a facehugger (it was cut out of him before it matured and made its own exit), and I thought there was a lot of interesting stuff going on here, most of which I enjoyed.

What I didn’t like was the art by Salvador Larroca. To give him some credit: the aliens look good and some of the action sequences, like the guy getting his head blown off with a shotgun, are nicely done. But where Larroca really falls down is in his drawing of the human characters, and particularly their faces. Everyone seems made of plastic, or like they’re the product of an AI art-generator, and not a very advanced AI program either. (I also thought the colorist was a program, as the credit is to Guru-eFX, but apparently that’s a real person.) Emotion doesn’t register at all, even when characters are yelling or screaming, and there’s little sense of movement in the way the figures are drawn. From what I’ve been able to gather, there’s a lot of strong opinions on Larocca out there in the comic community and I can only say that while I can see some people liking his style it’s not my thing and it took my grade on this comic down quite a bit.

But if you’re a fan of the franchise I’d definitely recommend this just for the story. You may not like the art any more than I do, but it’s something you’ll be able to put up with.

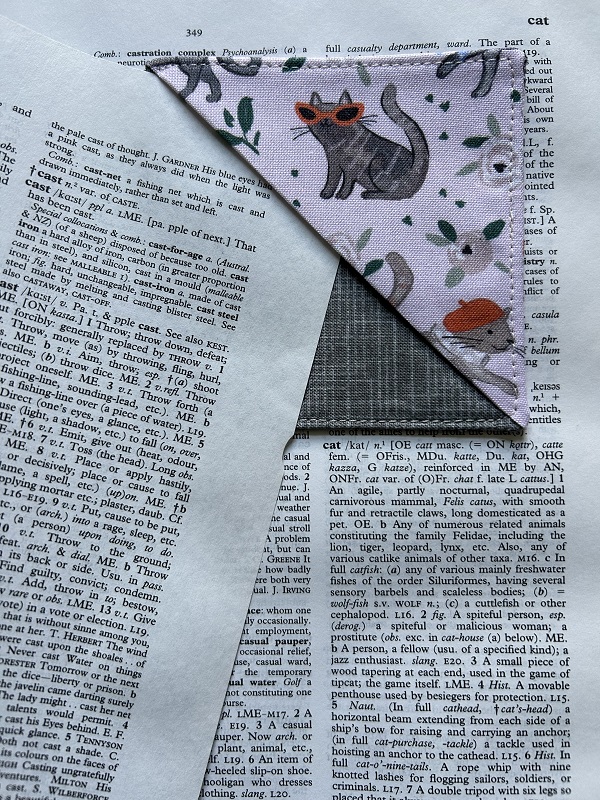

Bookmarked! #49: Kitty Corner

This is a particular kind of bookmark where the page slips into a cloth pocket. They go by different names, but this one, by Dane Jane Designs of Cambridge, is called a corner bookmark. I thought it made sense to pair it with “cat” in the OED, which made for an awkward entry at the top of the page. Oh well.

Book: The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

Marple: The Four Suspects

I think every mystery story is a magic trick, with the author trying to put one over on us. The challenge is to try and catch their sleight of hand and guess how the trick is being done before the big reveal.

As with a magic act, one of the key tools is misdirection. And, again as with a magic act, the audience knows it’s being misdirected, just not how. So it’s all a dance of deception.

We’re back in a familiar setting here, with the regular gang of friends getting together to solve a mystery put to them by Sir Henry Clithering, ex-Commissioner of Scotland Yard. One thing that’s changed since the Tuesday Night Club started up, however, is that now everyone defers to Miss Marple and her method for coming to a solution. Which she employs again here by decoding some British gardening slang (which is itself a kind of misdirection). But Christie plays fair with the clue we get, even pointing it out, and if I’d put enough thought into it even I might have twigged to what was going on.

The thing is, when our Jane points out the clue you immediately have to wonder if she’s directing us to something important or if we’re being presented with a red herring. But seeing as it’s Miss Marple herself who draws it to our attention, you can probably take it to the bank. Where the misdirection comes in is when the killer attempts to put the police on a false trail. The killers in mystery novels are magicians too, and especially in Christie where they have a real thing for putting on a show, complete with costumes, disguises, and other props.

Day by day

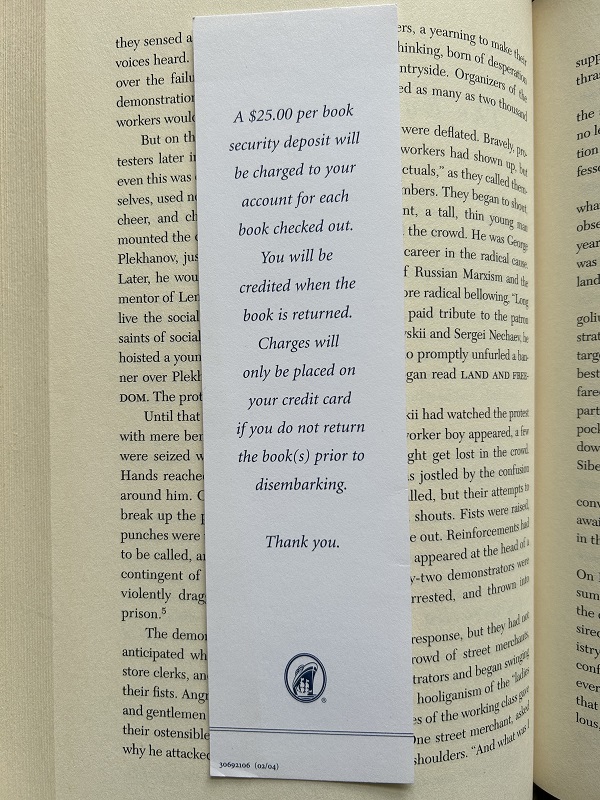

Bookmarked! #48: Bon Voyage!

I’ve never been on a cruise. But I know people who have. I guess some cruise ships have small onboard libraries, even though print is about as dated now as the age of sail.

Anyway, if you took a book out of this ship’s library they gave you a bookmark as a reminder to bring it back. As if that $25 deposit wasn’t enough of an incentive. That seems pricey to me.

Book: Angel of Vengeance: The “Girl Assassin,” the Governor of St. Petersburg, and Russia’s Revolutionary World by Ana Siljak