Not many houses in my area go all out with Halloween decorations. I thought these guys did the most. They really went to town with the inflatable stuff. I wondered why a hatchet buried in a skull would be bloody, but then skulls don’t have eyeballs either. Otherwise we’ve got a pair of really tall witches and a ghost and some jack-o’-lanterns. The one inflatable I thought was out of place was the Minion. What’s he doing in here?

Bookmarked! #64: Scary Stuff

Halloween coming up so here’s a spooky themed bookmark for you. I think Pet Sematary is one of King’s best books so I didn’t mind splurging a few bucks for this one.

Book: Zombies! Zombies! Zombies! ed. by Otto Penzler

The Immortal Hulk Volume 5: Breaker of Worlds

The Immortal Hulk Volume 5: Breaker of Worlds

Another Immortal Hulk volume, another up-and-down ride. I liked the main storyline, which had the Hulk squaring off against the Hulk-hunting Shadow Base headed up by Major Fortean, who is now wearing the Abomination’s hide like a kind of symbiote. That was all well set-up and had some good action to it, albeit action of a kind that, if you’ve been following this series, is starting to feel a little stale. More bodies melting into grotesque forms and then getting killed but not really being killed because they just end up being sent to that limbo beyond the green door. Still, issues #21-24 were solid. But then issue #25 took off in another direction entirely, jumping “eons” ahead into the future with the Hulk eating the Sentience of the Cosmos and a giant Hulk becoming a god – the “Breaker of Worlds.” I mean, literally. He flies through space and crushes a planet. There’s a survivor of this Hulk apocalypse though and we’re left with the promise that veteran Hulk enemy the Leader has plans to address the situation. Which at this point you really have to wonder at.

Another Immortal Hulk volume, another up-and-down ride. I liked the main storyline, which had the Hulk squaring off against the Hulk-hunting Shadow Base headed up by Major Fortean, who is now wearing the Abomination’s hide like a kind of symbiote. That was all well set-up and had some good action to it, albeit action of a kind that, if you’ve been following this series, is starting to feel a little stale. More bodies melting into grotesque forms and then getting killed but not really being killed because they just end up being sent to that limbo beyond the green door. Still, issues #21-24 were solid. But then issue #25 took off in another direction entirely, jumping “eons” ahead into the future with the Hulk eating the Sentience of the Cosmos and a giant Hulk becoming a god – the “Breaker of Worlds.” I mean, literally. He flies through space and crushes a planet. There’s a survivor of this Hulk apocalypse though and we’re left with the promise that veteran Hulk enemy the Leader has plans to address the situation. Which at this point you really have to wonder at.

I suppose this could all go somewhere interesting so I won’t outright condemn it. But I don’t personally care for Marvel titles when they go cosmic. I feel like they always lose the plot whenever a character becomes a god, from Dark Phoenix on down. I like it when they keep things simple. But there’s a sort of inflation built into most comic storylines, you also see it in a lot of manga, where you have to keep pumping things up until in some cases (like this) you get to a point where they collapse under the weight of some vision of infinite power.

That certainly seems to be what’s happening here. But I’ll continue.

The good old days 2

The next page in this book of reflections follows up on a point raised in my previous post: what happens to milk that the delivery guy leaves on someone’s porch if it’s either too hot or too cold out? I think someone had to be home to bring it inside. But luckily, mom was right there in the kitchen, making dessert!

As I grew up on a dairy farm we did not have milk delivered. We did, however, skim the cream from the milk and churned our own butter out of it. And made our own ice cream. I ate a lot of ice cream in those days. And drank a lot of milkshakes.

Road trip 1

The Approach

The Approach

A mid-size airport is nearly shut down due to a massive winter storm. Then a small engine-prop plane flies in out of nowhere, crashing and exploding into a fireball on landing. A body is pulled from the wreckage. Later, that body comes to life, transformed into a flesh-eating, tentacle monster. It kills people and gets bigger, and bigger. I mean, it grows like a Xenomorph. An old lady worships it, reciting Lovecraftian catch-phrases (“Yoth anon par a koth . . . Shun ara soth”). The skeleton crew at the airport, apparently cut off by the storm from any help, set out to hunt the beast down and kill it.

A mid-size airport is nearly shut down due to a massive winter storm. Then a small engine-prop plane flies in out of nowhere, crashing and exploding into a fireball on landing. A body is pulled from the wreckage. Later, that body comes to life, transformed into a flesh-eating, tentacle monster. It kills people and gets bigger, and bigger. I mean, it grows like a Xenomorph. An old lady worships it, reciting Lovecraftian catch-phrases (“Yoth anon par a koth . . . Shun ara soth”). The skeleton crew at the airport, apparently cut off by the storm from any help, set out to hunt the beast down and kill it.

Like a lot of the horror comics from Boom! Studios, The Approach very much feels like a 1980s horror flick, most obviously in this case John Carpenter’s The Thing. And having spent a good chunk of my teenage years enjoying those movies, I’m not saying that’s a bad thing. I thoroughly enjoyed the story here by Jeremy Haun and Jason A. Hurley precisely for its most familiar (to me) elements. What pulled it down a couple of notches were two things.

In the first place, I thought they threw too much stuff into the pot. The story could be continued at the end (yes, you get a final panel/shot that suggests the monster isn’t all dead yet), but it seems pretty complete otherwise and there are two major points that are introduced that receive no explanation whatsoever. First: the plane that crashes is said to have gone missing 27 years earlier, so it not only appears out of nowhere but out of no-when. Where, or when, was it all that time? No idea. Nothing more is said of the matter. Second: does the old lady who chants to the monster know something about its provenance? Or is she just a gibbering idiot? Again, no idea.

The second reason I’d knock it down is the art. Jesús Hervás took over from Vanessa R. Del Rey as the artist of the Empty Man series in The Empty Man: Recurrence and The Empty Man: Manifestation, and I’ve already said I’m not a fan. He definitely has his own style, I give him credit for that, but it’s really not my thing. It’s just too hard to figure out what’s going on in a lot of the action scenes. And the monster here looks (and sounds) too much like the buggy creatures in The Empty Man. It’s just not that interesting.

But despite being full of stuff that isn’t explained and having a plot that’s so predictable I was calling how it was going to end by page 6 I still enjoyed this. I don’t know if it would appeal as much to people who weren’t students of ‘80s horror though.

Bookmarked! #63: Bookmark Like an Egyptian

Actually, I don’t think the ancient Egyptians used bookmarks because they didn’t have books. They kept written works on scrolls.

This is kept in a plastic sheath because it’s painted on papyrus, and it’s very thin and delicate. I can’t remember where I got it, but it wasn’t Egypt. So most likely some museum.

Book: A World Beneath the Sands: The Golden Age of Egyptology by Toby Wilkinson

The good old days 1

Just got back from a visit to a Long Term Care facility where this book on insights into how the world has changed was lying around. It all seemed impossibly long ago, but the thing is, for my parents’ generation milk delivery was a reality, and there were still horse-drawn wagons being used both on the farm and in the streets.

I’ll post a few more of these in the weeks ahead.

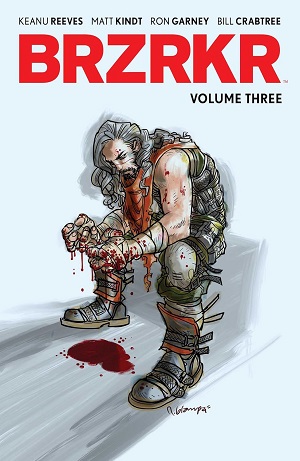

BRZRKR Volume Three

BRZRKR Volume Three

If you read my review of BRZRKR Volume Two you’ll know I went into this final part of the trilogy with really low expectations. Expectations that were, in the event, barely met.

If you read my review of BRZRKR Volume Two you’ll know I went into this final part of the trilogy with really low expectations. Expectations that were, in the event, barely met.

On the plus side, this is a really fast read. There isn’t a lot of talking, and what there is can be ignored, so you’re basically just flipping the pages looking at Ron Garney’s explosive art. And by that I mean there are lots of explosions.

Our hero B (or Unute, or Keanu Reeves) is feeling tapped out, so now’s a good time to introduce a Lady Berserker, a scientist guy who turns himself into a Berserker, and finally a pair of Berserker twins who are heading off at the end to grow and plant their seeds. Which sounded kind of creepy, but what do I know. Meanwhile, Unute becomes mortal but then is reborn so he’s immortal again and at the end he’s back on another planet or in another dimension or something.

No, none of this makes any sense. It might mean everything and nothing. And of course the story is left open-ended. I guess the Berserker twins could go on to have further adventures and the bad guy could re-assimilate and come back to haunt them. But I’m out. Some readers (especially if they’re fans of the Tao of Keanu) might still find the elevation of an action hero into a god interesting or even deep, but I feel like it’s been done to death and overall this struck me as one of the laziest comics I’ve read in recent years. So even if they do go on I won’t be hanging with it.

We’ll always have Colmar

This pretty place is Colmar, France. If you do an image search for Colmar you’ll find this same picture coming up again and again. So maybe these colorful houses on this one street are all there is to see in Colmar. I don’t know as I’ve never been there. I just did the puzzle. Which had one piece missing! See if you can spot it. Argh.