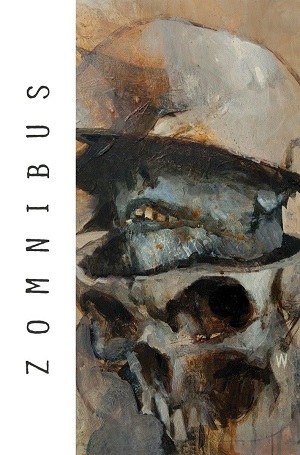

Zomnibus

The title actually means something here, as this is an omnibus edition of three very different comic series, all dealing with zombies. It’s a bit unevenly weighted though, as the first two series are pretty standard after-the-apocalypse, Walking Dead kind of stuff, while the third is billed as the “Complete Zombies vs. Robots,” which is something else entirely. So let’s break it down.

The title actually means something here, as this is an omnibus edition of three very different comic series, all dealing with zombies. It’s a bit unevenly weighted though, as the first two series are pretty standard after-the-apocalypse, Walking Dead kind of stuff, while the third is billed as the “Complete Zombies vs. Robots,” which is something else entirely. So let’s break it down.

Feast!: this was a very meat-and-potatoes zombie story. A busload of dangerous convicts crashes just after the zombie apocalypse, leaving the cops and cons having to work together to survive. They wind up in a small town where some other survivors have boarded up a building hoping to ride things out. The usual small-group dynamics and power struggles ensue as the number of survivors gets whittled down.

Being a fan of all (or most) things zombie, I enjoyed reading it. And the downbeat ending helped give it a bit more punch. Because all things considered, there was nothing exceptional about it.

Eclipse of the Undead: I mentioned in my lede how the first two stories here are standard zombie stuff, and evidence for that includes the way characters in both recognize immediately that they are living in a world already defined by the rules laid down in zombie movies. In “Feast!” the first character to twig to what’s going on says “You fuckers ain’t ever watched the movies? Zombies, man . . . Zombies!” In this story, while nobody knows how it happened, the zombie apocalypse is old news on arrival. “We saw them in the movies, in the funnies, we were almost used to them – a joke like Frankenstein or Dracula – but the fact is . . . the dead came back.” Specifically, George Romero’s living dead came back. Welcome to the metaverse.

The story in “Eclipse” (so titled because there is an eclipse, though I don’t know what the significance of that is) is even more basic than “Feast!” What we have is a bunch of people, abandoned by the military, breaking through the zombies besieging their refugee camp, which has been set up in the Los Angeles Coliseum. The usual small-group dynamics and power struggles ensue. The same good-guys and bad-guys having to work together, or falling out in ways that lead to their destruction.

I guess this was OK, but again there was nothing new about it. Even the old samurai guy seemed like a cliché.

The Complete Zombies vs. Robots: here we have the meat and the brains of this particular zombie feast. A now classic comic written by Chris Wyall and illustrated by Ashley Wood, Zombies vs. Robots is fun, smart, and looks great. I don’t know if the series is complete even now though, so I don’t know how accurate the title is. What you get here are the first two volumes: Zombies vs. Robots and Zombies vs. Robots vs. Amazons.

This is not a comic you can just breeze through. The first time I read it, which was I guess fifteen years ago, I remember being confused as to what was even going on. There’s a complicated plot that involves time-jumping and the unexplained appearance of mythical beasts to join in the fun. I don’t think there are layers to the story though, and it’s enough to just enjoy the general parallel drawn between “the inhuman and the no-longer-human.” Or as the first page breaks it down: “Zombies! Braindead automatons and rotting reminders of man’s hubris! Robots! Brainless automatons and constructed remainders of man’s potential!” That’s great stuff.

If I were to sort it out a bit, I thought the first volume was the best. I love the possessed warbot that looks like a cross between R2-D2 and a tank, with a Punisher logo for a face. I couldn’t really figure out where the Amazons were coming from in the second volume, and didn’t think they were as interesting as the scientists. But it still played well and I thought it made an original contribution to the annals of zombie lore. Alas, I’ve heard rumours of a movie being in the works, and I don’t see how that will pan out. I guess all we can do is hope for the best.