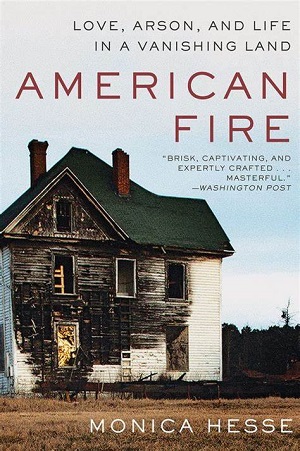

American Fire: Love, Arson, and Life in a Vanishing Land

By Monica Hesse

The crime:

From November 2012 to April 2013 arsonists Charlie Smith and Tonya Bundick went on a rampage through Virginia’s Eastern Shore. They ended up setting over 80 fires, mostly burning down abandoned homes. Upon their arrest, Smith pled guilty while Bundick maintained her innocence. Both were convicted and sentenced to long prison sentences.

The book:

The book:

I thought this was a terrific book, shining a light on a crime (arson) that probably doesn’t get as much attention as it deserves. Given just how prolific Smith and Bundick were as fire bugs, however, this was a fairly well reported case and one that tells us a bigger story, which is what drew Hesse to it. “Big-name crimes have a way of becoming big names not only because of the crimes themselves, but because of the story they tell about the country at the moment.”

That story is the familiar one of a rural region suffering from long-term economic decline. This was reflected both in terms of the Eastern Shore’s population, which actually declined nearly 20 percent from 1910 to 2010, as well as in the nature of its industry, with potato farming replaced by chicken processing plants. Compared to the rest of the state, the Eastern Shore had lower numbers of college graduates as well as lower incomes, all of which helped make it a tinder box.

“In November of 2012, the Eastern Shore of Virginia was old. It was long. It was isolated. It was emptying of people but full of abandoned houses. It was dark. It was a uniquely perfect place to light a string of fires.” All you had to do was strike a match and you’d have a story perfectly suited for what political observers were beginning to take note of as one of twenty-first century America’s defining qualities. “America fretted about its rural parts, and the arsons were an ideal criminal metaphor for 2012.” The Eastern Shore was Evan Osnos’s Wildland, or Donald Trump’s landscape of American carnage. It was the land of the left behind, and in this case that meant left behind to burn.

I have to wonder if I would ever have read or heard anything about some of these places if not for being a fan of true crime. The declining population of the Eastern Shore immediately reminded me of the similarly stagnant or falling numbers in South Carolina’s Lowcountry as described in Valerie Bauerlein’s account of the Alex Murdaugh murder case The Devil at His Elbow. Reading both books I found myself having to consult atlases to familiarize myself just with the location of their depressed regions, as I knew nothing at all about them. And I suspect I’m not alone in that. These are places most people don’t even drive through on their way to somewhere else.

In addition to the political allegory, American Fire is also a love story. To be sure a crazy, tragic sort of love story, but then love itself is always a bit bonkers and frequently ends in tears. The specific kind of crazy here wasn’t so much a case of folie à deux or shared criminal conspiracy like Bonnie and Clyde (though these paradigms are discussed) as it was a neo-noir. Seen through this lens, Charlie and Tonya are easily identifiable genre types: the lovestruck, hard-luck loser and the mysterious, corrupting femme fatale.

“The psychologists who study criminal couples have discovered that the partnerships are rarely equal ones. The crimes are usually spurred on by one dominant partner.” And that’s definitely the takeaway here. It was clear not just to everyone but to Charlie himself that Tonya was out of his league. He’d noticed her at bars but wisely “avoided her on purpose. Women like that he always ended up making himself a fool in front of, and it seemed safer to stay away entirely.” Alas, easier said than done, and one fateful night, with only “an eight ball of cocaine in his pocket and a vague plan to kill himself,” they hooked up. You could even say she saved his life.

Things might have worked out, but Tonya seems to have always wanted something more while Charlie’s insecurities developed into performance issues. Inadequacy and low self-esteem led to impotence. Or as he put it, his belief that she was too good for him led to his dick not working. After a while it seemed the only way she could get her kicks with him was by their driving around setting fires together. Arson became a surrogate for sex. And whatever else you want to say about that as a basis for a relationship, it’s basically unsustainable. After a while you’re going to run out of fuel.

It’s this love story that I think is the real selling point for American Fire. Hesse actually makes both Charlie and Tonya into sympathetic figures, though her dislike for Tonya does come through in some uncharitable comments at the end. My own sense was that their love and their crimes were both representative of the human wreckage left behind by the fires that have been burning in America for the past fifty years. And not always burning in such a spectacular fashion, but with Robert Frost’s “slow smokeless burning of decay.”

Noted in passing:

“It’s amazing how boring trials can be. How even the most salacious of crimes committed under the most colorful of circumstances can result in testimony that is tedious and snoozy.”

This is why we have books, and why books have editors.

Takeaways:

As flattering as it is to have a woman who is clearly out of your league taking an interest in you, you need to see it as a red flag. Charlie should have trusted his gut, as it’s safer “to stay away entirely.”

True Crime Files

I think the Asterix comics were all stand-alone stories. At least I never thought there was any sort of continuity in the series. But as things kick off here we have Panoramix heading into the Forest of the Carnutes for the annual druid convention, which is an event that had been foreshadowed in the previous volume, Asterix and the Golden Sickle. What set the ball rolling in that story was that Panoramix had broken his sickle just before the meeting of druids in the Forest of Carnutes. So it does feel like there’s a shared timeline in place.

I think the Asterix comics were all stand-alone stories. At least I never thought there was any sort of continuity in the series. But as things kick off here we have Panoramix heading into the Forest of the Carnutes for the annual druid convention, which is an event that had been foreshadowed in the previous volume, Asterix and the Golden Sickle. What set the ball rolling in that story was that Panoramix had broken his sickle just before the meeting of druids in the Forest of Carnutes. So it does feel like there’s a shared timeline in place.