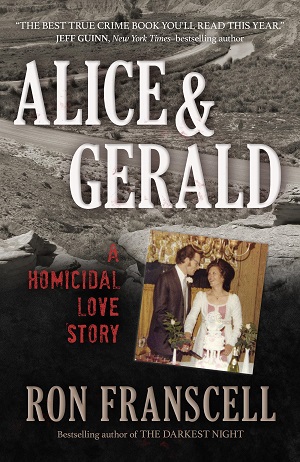

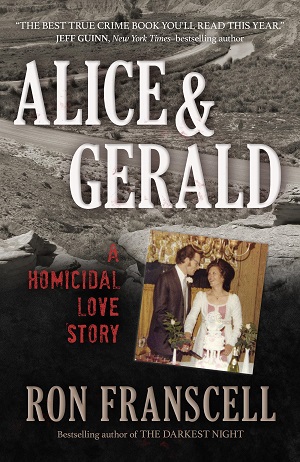

Alice & Gerald: A Homicidal Love Story

By Ron Franscell

The crime:

In 1976 Alice Prunty met Gerald Uden and they were married soon thereafter. It was the fourth marriage for both, and both had children from their earlier marriages. What Alice didn’t tell Gerald until after the wedding is that she’d killed her last husband, Ron Holtz, claiming abuse at his hands. Gerald was understanding. Later, Gerald became tired of making support payments to his ex-wife Virginia, who had custody of his two sons. So, perhaps egged on by Alice (who disliked his ex-wife intensely), he killed all three of them in 1980.

Authorities strongly suspected Alice of killing Holtz and Gerald of the triple homicide of Virginia and his two sons, but none of the bodies were found so after moving to Missouri the homicidal couple went on living the rest of their lives in peace as the case grew colder. But police never lost interest in it, and after much digging around (literally and metaphorically) they managed to find Holtz’s body where Alice had thrown it in an abandoned mine shaft. That was in 2013. Alice was charged and convicted of Holtz’s murder and would later die in prison. Gerald would confess to the murder of Virginia and the two boys and be sentenced to several life sentences. The bodies of his victims were never found.

The book:

The book:

By coincidence I came to Alice & Gerald after reading a series of books about criminal couples, each of which raised the same question about the apportioning of guilt. Here’s a recap:

The Art Thief by Michael Finkel: Stéphane Breitwieser and Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus lived together and had a side hustle stealing works of art from museums all around Europe. Anne-Catherine seems to have operated mostly as a lookout while Stéphane did all the work.

Guilty Creatures by Mikita Brottman: Brian Winchester killed Denise Williams’s husband Mike and then married her. After a few years together they split up and Brian copped a plea, implicating Denise in Mike’s murder. She was initially found guilty of first degree murder but then had the judgment overturned, though her conviction for being an accessory to murder remained.

American Fire by Monica Hesse: starting in November 2012 Charlie Smith and Tonya Bundick went on a months-long arson spree, burning abandoned homes on Virginia’s East Shore. At trial, Smith claimed he did it all for love and that torching houses was Tonya’s thing. Tonya didn’t have much to say.

In Alice & Gerald the issue of who was the dominant partner is again raised, and it seems as though most of the people close to the case agree that Alice was the one pulling the strings. That’s the sense I had as well, but it’s possible that the way Ron Franscell was telling the story led me to that conclusion. Plus, after reading some of the discussion in Guilty Creatures, I was on my guard against the “Eve factor”: “The way that when a man and a woman are part of a crime together it is generally the woman who is thought to be the mastermind, the Eve who tempts Adam.”

What makes it hard to say in the case of Alice and Gerald, especially given how cold a case it was, with the murders having taken place forty years before being brought to trial, is the fact that Alice played everything close to the chest. In this she was very much like the women in the other cases I just mentioned. Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, Denise Williams, and Tonya Bundick all clammed up after their arrest, not talking to police or to reporters. If nothing else, this suggests they were at least smarter than their partners in crime. As I’ve said before, if you’ve been arrested, for pretty much anything, the best thing you can do is keep your mouth shut. Taking this principle a step further, I was particularly impressed by the fact that Alice refused to take a polygraph or lie-detector test as “a matter of principle.” When Gerald was later brought in for questioning he kept to the same line: “No polygraph. It’s not about my guilt or innocence. It’s just a matter of principle.” The detective questioning Gerald noted the similarity in response and assumed, probably correctly, that they’d been coaching each other. But, for them, this was absolutely the right move. In the first place, polygraphs are worthless (Alice later told investigators that she’d researched them and found they were “notoriously unreliable”), and in the second they didn’t want to answer questions or talk to the police anyway.

On the question of guilt, you could argue it either way. Taking Alice’s side, her murder of Ron Holtz could be seen as being what she said it was: a response to domestic abuse. Holtz was a violent head case who had spent a lot of time in mental hospitals (which is where he met Alice, where she worked as a nurse). On the other hand, Alice was a killer before she even met Gerald, and given her hatred of Virginia it’s hard to believe she wasn’t encouraging Gerald to do something to get rid of her. And it’s also pretty obvious that she knew what Gerald had done after the fact and didn’t just keep quiet about it but helped him to cover his tracks by writing phoney (and cruel) letters to Virginia’s mother.

In sum, while it’s hard to say who was the dominant partner I think the evidence shows that neither of them had much in the way of empathy, and thought nothing of murder as a way to dispose of people they found to be an inconvenience. Or an unnecessary expense. Gerald reckoned killing his boys would lead to savings in child support of $14,000: “He knew because he’d added it up: $150 for ninety-two more months.” As one of Alice’s children put it when describing his reaction to first meeting Gerald, “This guy is really weird. Not like a child molester weird or anything, just spooky weird . . . just spooky. . . . Like he has no feeling.” Not stupid then, but missing something.

I’ll confess that when I started in on Alice & Gerald it put my back up a bit. The Prologue felt overwritten in its evocation of place:

Wyoming [in the 1960s] was a place to land without baggage, where one could hide and never be found, a kingdom of dirt where giant hollows in the earth might swallow up a man (or woman) entirely, an ambiguous landscape of infertile dreams and pregnant hopes. The landscape was vast, desolate, and mysterious, festooned with hidey-holes that were forgotten or never known.

It was a spot on the edge of the Big Empty where your dog could bark forever or you could piss on the side of the road or shoot your gun at the moon or call yourself by another name. None of The World’s ordinary rules applied. Whatever your badlands fetish, you could practice it unmolested in this impossibly empty place.

I rolled my eyes at “infertile dreams and pregnant hopes,” but after a while Franscell’s voice grew on me. A native of Wyoming, he writes in a way that brings out the local colour. Here, for example, is his description of the spot where Virginia and the two boys will be murdered: “Virginia pulled off into the cheatgrass shoulder this side of the canal. The water ran sluggish and buckskin brown, full of sandrock dust, caliche, horseshit, and other high plains compost. There was so much dirt in the channel that you could damn near plow it.” In other places I had to look up the meaning of “butt-sprung” (old and worn out), and shook my head, smiling, at squalls that “can strike faster than a rattler on meth.” I entered into the spirit of this enough so that in a later ode to the “impossibly empty place” that is Wyoming I had no problems at all. And there was an important point being made connecting the murders to the desolate geography.

Wyoming poses a unique challenge for cops in all missing persons cases, cold nor not.

Anybody who’s driven through Wyoming’s boundless terrain has imagined how easy it would be to lose oneself in int.

And more than a few have fantasized about losing someone else out there.

The state’s average population density of six people per square mile (in contrast, New Jersey has 1,200 people per square mile) is an unfair mathematical measure. In fact, the state encompasses thousands of square miles where nobody lives, nobody goes, and nobody ever will.

In other words, Wyoming – the least populous and most incomprehensible of the lower forty-eight states – is the baddest of badlands. There are more places to hide dead people than live people will ever find.

Given this bad-ass landscape, all the more credit goes to the dogged police work that had to persevere through generations of different investigators to finally dig out the truth. They didn’t have much to go on, aside from their conviction that Alice and Gerald were guilty as hell. This was something that was obvious right from the first interviews they sat down for at the time of the murders, and it was reinforced in every subsequent interaction. But how to prove their guilt? For that the police would need a body, and even after identifying the probable location of Ron Holtz’s final resting spot, recovering his remains wasn’t easy, or cheap. It’s not often that I get a chance to compliment the police in these True Crime Files, so I’m happy to give them a shout out here.

In addition to the police work there was also the concern of Virginia’s mother, Claire, who did everything she could to keep the investigation going. “The universe loves a stubborn heart,” is Franscell’s tributary line. In a lot of the cases I’ve talked about you’ll find family members taking on this kind of a role. Mike Williams’s mother in Guilty Creatures and Kari Baker’s “angels” (her mother and sisters) who refused to accept the coroner’s verdict of suicide in her death (as recounted in Kathryn Casey’s Deadly Little Secrets). The sad irony is that Claire died shortly before Alice and Gerald were brought to justice, and the bodies of Virginia and the boys were never found. Instead, what undid the killers was the discovery of Holtz’s body, a man who nobody seemed to care about. Indeed, when the police tried to follow up on Holtz’s disappearance they found that his family were “so unconcerned about their son and brother, who’d been such an asshole all his life, that nobody even reported him missing.” The wheels of justice sometimes turn in mysterious ways.

Noted in passing:

The invocation of Shakespeare to lend weight to what are often just sleazy stories of domestic violence can be overdone. I mentioned this in my review of Guilty Creatures and it comes up again here. One of the three epigraphs comes from Macbeth: “The attempt and not the deed confounds us.” It’s a quote I’ve used myself on occasion, but what relevance does it have here? Alice and Gerald weren’t undone by their attempt to commit murder, but by the discovery of Holtz’s body. They weren’t convicted of attempting anything, but of committing murder. Then in his Acknowledgments Franscell refers to this as a “bizarre story of Shakespearean proportions.” How so? Bizarre yes, and tragic for the victims. But in what sense are the “proportions” Shakespearean? Does he mean heroic? Larger than life? Because I don’t see either.

The only point when I did feel Shakespeare’s presence was when Gerald confessed to shooting Virginia and his two sons in the head, with the unfortunate result that their bodies bled all over the inside of his car. “They didn’t suffer. But I had no idea the human body contained that much blood,” he tells the investigators. That does sound like an echo of Lady Macbeth’s “Who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?”

When the police had Alice nailed for the murder of Ron Holtz there was renewed interest in the premature death of her previous husband, ascribed at the time to hypertension and kidney failure. The husband’s corpse was exhumed so that pathologists could test for the presence of ethylene glycol in the tissues.

Ethylene glycol is the primary compound in ordinary automobile coolants and antifreezes. In the past century, it has also been a favorite poison – especially for husband-killing wives, according to forensic data – because it’s in every garage, it’s colorless and odorless, it tastes very sweet, and its toxic effects can be misdiagnosed as something else.

I guess if the forensic data says this is the poison of choice for husband-killing wives then it must be true. It was a point that made me think of the story “Antifreeze and a Cold Heart” in the collection Murder, Madness and Mayhem by Mike Browne about a woman who killed two husbands this way. Husbands may want to keep the antifreeze locked up if they think their marriage is on the rocks.

Takeaways:

One violent person without a conscience is bad enough, but when they find a soulmate it’s double trouble.

True Crime Files

After the initial run of Swamp Thing comics ended, along with Swampy’s brief sojourn with the Challengers of the Unknown (covered in The Bronze Age Volume 2), it looked as though the character was going to be left on the shelf for a while. Luckily, DC changed their mind and so we got a new series titled The Saga of the Swamp Thing, which was written by Martin Pasko. This omnibus edition presents #1-19 of that run, along with The Saga of the Swamp Thing Annual #1, which is a comic adaptation of Wes Craven’s 1982 movie and doesn’t really fit into the canon.

After the initial run of Swamp Thing comics ended, along with Swampy’s brief sojourn with the Challengers of the Unknown (covered in The Bronze Age Volume 2), it looked as though the character was going to be left on the shelf for a while. Luckily, DC changed their mind and so we got a new series titled The Saga of the Swamp Thing, which was written by Martin Pasko. This omnibus edition presents #1-19 of that run, along with The Saga of the Swamp Thing Annual #1, which is a comic adaptation of Wes Craven’s 1982 movie and doesn’t really fit into the canon.