We’re keeping it small and simple this week!

Book: The Hound of the Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle

We’re keeping it small and simple this week!

Book: The Hound of the Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle

Had our heaviest snowfall of the year this morning. Going to be a lot of digging out. And I just want to salute the delivery people who keep going even in these bad conditions. There’s a fellow who delivers newspapers that I always wave to when I’m out walking in the morning around 4:30 am (I’m an early bird). He just has a tiny car and it was half buried in some of the roads he was going through today. That’s not an easy job and it doesn’t pay anything, so give these guys some credit. (You can click on the pics to make them bigger.)

Introducing Mycroft Holmes. And he’s just one of the odd things about this story.

To begin with Mycroft, Watson starts things off by saying how he knows nothing of his friend Sherlock’s family, a deficit that gets corrected when Holmes freely offers up that he has a brother who is even more advanced in detective analysis than he is. Which leaves me to wonder why Mycroft had been kept a secret to this point. Unlike the way he is usually portrayed, which is as a sibling rival, the two seem to get along famously. Holmes also says that many of his “most interesting cases” have come to him by way of Mycroft. So it seems strange that his name, or existence, hadn’t come up at any point before this.

Another odd thing with regard to Mycroft is that he is described as being incorrigibly lazy, a man of “no ambition and no energy.” This is fine (hey, I can relate!), and it’s not surprising that there should be another eccentric in the family. But then for the rest of the story Mycroft becomes a man of action more than up to the business of chasing around London wrapping things up with Holmes and Watson and Gregson.

Moving away from the character of Mycroft, another odd thing about the story is the ending. In other Holmes adventures there’s been a quick coda that lets us know what happened to the bad guys if they hadn’t been immediately apprehended. For example, in the previous story collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, “The Resident Patient,” we’re told that the trio of baddies died in a shipwreck.

In this case, despite Latimer and Kemp being two of the most vicious villains in the canon, they both get away, and with Sophy! To be sure, there is a postscript about a pair of Englishmen traveling with a woman in Hungary. They are both stabbed to death, and when Holmes reads about their murder he supposes that Sophy has taken her vengeance on her abductors. We’re not given any idea though why he would think this, or how Sophy managed to do it (Latimer, for one, is described as being a strapping fellow), or whatever became of Sophy herself in the end.

“And this was the singular case of the Grecian Interpreter, the explanation of which is still involved in some mystery.” I’ll say. It’s a good read though and plays off expectations in some interesting ways (for example, instead of Holmes helping a pair of youngsters get together he’s more interested in keeping them apart). It also has darker shadows than most of the other stories in the canon, shadows that even the introduction of Mycroft can’t quite dispel.

As a general rule when I do puzzles I put together the outside first. Another easy part to do is a skyline if there is one in the picture. This puzzle had a clear division between the flowers and the sky, which was pretty easy to put together. Then, since there wasn’t a lot of sky, I was able to fill it in first. The flowers were a lot harder.

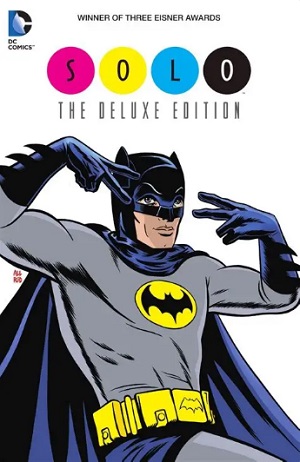

Solo was a limited run of comics consisting of a dozen 48-page issues, with each issue being illustrated by a different artist. Some of the biggest names in the biz were recruited and given creative freedom to tell whatever stories they wanted, using DC characters as they saw fit. In some cases the artists also wrote their pieces but they also worked with writers. This Deluxe Edition collects the complete run.

Solo was a limited run of comics consisting of a dozen 48-page issues, with each issue being illustrated by a different artist. Some of the biggest names in the biz were recruited and given creative freedom to tell whatever stories they wanted, using DC characters as they saw fit. In some cases the artists also wrote their pieces but they also worked with writers. This Deluxe Edition collects the complete run.

Here’s the line-up:

#1 Tim Sale (with Jeph Loeb, Brian Azzarello, Darwyn Cooke, and Diana Schutz)

#2 Richard Corben (with John Arcudi)

#3 Paul Pope

#4 Howard Chaykin

#5 Darwyn Cooke

#6 Jordi Bernet (with John Arcudi, Joe Kelly, Andrew Helfer, Chuck Dixon, and Brian Azzarello)

#7 Mike Allred (with Laura Allred and Lee Allred)

#8 Teddy Kristiansen (with Neil Gaiman and Steven Seagle)

#9 Scott Hampton (with John Hitchcock)

#10 Damion Scott (with Rob Markmam and Jennifer Carcano)

#11 Sergio Aragonés (with Mark Evanier)

#12 Brendan McCarthy (with Howard Hallis, Steve Cook, Trevor Goring, Robbie Morrison, Tom O’Connor and Jono Howard)

I’ll say right away that the art here is great. I have my favourites and others that I didn’t like nearly as much, but I have to acknowledge that even the ones that weren’t my thing were highly creative. As a portfolio of some of the best people working at the time (the series ran from 2004 to 2006) it’s a treasure chest.

That said, I really didn’t think much of most of the stories. They’re all over the map in terms of genre and tone, even within some of the individual issues. And a lot of the time they just felt like flimsy excuses for the art. Which I guess you should expect in what was a consciously art-driven project. Darwyn Cooke won an Eisner Award for his issue and I had no disagreement with that, as in my notes I had it down as one of the best. But overall I thought there were more misses than hits when it came to what was actually being illustrated, and I can’t say that any of the stories stayed with me for long.

Just as a final note, I have no idea why, for such a deluxe hardcover edition, they put Mike Allred’s drawing of Batman doing the Batusi on the cover. That’s no way to sell a book.

Over at Good Reports I’ve posted “The Last Canon,” which is the first essay I’ve written in years. It’s a return to a question I wrote about 25 years ago (yes, it’s been that long!): What are students who are studying English in university actually reading?

Back in 2001 I noticed that the books on the required reading lists for undergraduate courses were getting shorter. Since then we’ve been hearing a lot more about how students don’t, and in some cases can’t read as much.

This made me wonder: Just what books constitute the list of works that you would expect every student of literature will have read by the time they graduate? I’m not saying mine is a definitive list of great books, or even a list of the books that I think everyone should read, but I had fun playing with it.

In my review of the Visions of Poetry edition of Poe’s “The Raven,” illustrated by Ryan Price, I mentioned how I had memorized the poem as a kid from a Mad magazine adaptation. Well, the book I read that adaptation in was Utterly MAD. I’ve kept it around a long time now.

In my review of the Visions of Poetry edition of Poe’s “The Raven,” illustrated by Ryan Price, I mentioned how I had memorized the poem as a kid from a Mad magazine adaptation. Well, the book I read that adaptation in was Utterly MAD. I’ve kept it around a long time now.

The stories collected here are mostly long-form satires of established properties like Robin Hood, Tarzan, Little Orphan Annie, and Frankenstein. And then there are a couple of cultural pieces, one on adapting novels to the big screen and the other on supermarkets. The latter I guess being something new at the time (the book’s first printing was in 1956).

Most of the humour hasn’t aged well. There are a lot of little gags that play out on the edges, but the verbal ones especially don’t land. Plus I think you’d probably want to be acquainted with the source material. “G. I. Shmoe” is a take-off, I think, of a G. I. Joe comic, but I didn’t get the punchline every woman delivers where they ask him if he’s got gum. And “Little Orphan Melvin” won’t work unless you have some idea of the original characters, how they talk and relate to one another, and the sorts of situations Annie finds herself in. Other stories, like “Robin Hood” and “Melvin of the Apes” just weren’t funny. Maybe they thought the name Melvin was funny. Also the Yiddish word “fershlugginer.” Sometimes the crammed visual style does work passably well, as with the “Frank N. Stein” story and the trip to the supermarket, but overall it wasn’t working for me.

That said, I love this little paperback for two stories that, for whatever reason, have stayed with me. Obviously one is the adaptation of “The Raven.” This is typical of the crammed style I mentioned, with lots of different stuff going on in every cell, including a lot that’s totally unrelated to the poem, like a dog that outgrows the narrator’s apartment. But where I give them the most credit is in including the full text of the poem and having all kinds of fun with it, from emphasizing the fearfulness of the narrator, hiding in his room, to presenting the lost Lenore as a beefy, cigar-smoking lady who presses clothes. To some extent, I’m still not sure how much, this interpretation of the poem has for me become a part of it that I can no longer disentangle from what Poe wrote.

The second story that stands out is “Book! Movie!” This is meant to illustrate how Hollywood takes gritty, realistic novels and cleans them up, turning them into tinselly trash. Which is something that I think probably happened a lot more often in the 1950s than it does today. Anyway, the Book part tells the story of a loser living in terrible poverty who cheats on his wife and is caught by a blackmailer (though I don’t know what the blackmailer could be thinking he’d get out of it). The guy then kills his mistress and the blackmailer (with lots of “Censored” dots covering up the gouts of gore) and is pursued by demons back to his home, where he learns that his wife, who he hates, has invited her twin sister to live with them “forever.” The man collapses in despair, saying: “This miserable hopelessly hopeless situation is just perfect for a book ending.”

The Movie part turns the man and his wife into an affluent couple who even sleep in separate beds. As was the custom on screen at the time. The man is pursuing an affair (because he can’t stand that his wife is a slob), and is caught by a blackmailer. He then kills his mistress and the blackmailer with a revolver, which mysteriously doesn’t leave any traces of blood (the man in the Book story had used a knife). Returning home, his wife runs to his arms and says that from now on she’ll be a perfect helpmeet and keep a tidier house, and they skip off together over the rainbow while singing about joy.

As I say, I think this phenomenon of the Hollywoodized/sanitized novel is probably not as big a thing today, but the outline presented here has always stuck with me as a way of thinking about how page-to-screen adaptation works.

As for the cover, I’m not sure how well it would fly in the present age. Probably a little better than Token MAD, and in both cases I’m hoping the sense of irony would help it out.

This week’s bookmarks are brought to you by the fabulous Fraggle, who sent them all the way from the north of England. Gibside and Wallington Hall are both heritage sites and I was thrilled to see that the National Trust still have these embossed leather bookmarks in their gift shops. Because what’s a nicer keepsake than a bookmark? I still have a bunch of them from my visit to the UK in the 1970s (see some from Scotland here), but I don’t think I was ever in Northumberland or Tyne & Wear.

Book: A History of Britain: The British Wars 1603 – 1776 by Simon Schama

The Way Some People Die was the third of Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer novels and it’s remarkable how much his individual formula had already been set.

In the first place we have a woman coming to Archer with a problem. It’s the ladies who get the ball rolling. That’s how the first Archer short story, “Find the Woman,” kicks off, back when Archer was still “Joe Rogers.” It’s Elaine Sampson in The Moving Target, Maude Slocum in The Drowning Pool, and Mrs. Samuel Lawrence (more on that later) in this book.

Second: most of these women have the same problem they want Archer to solve. Millicent Dreen wants Archer to find her daughter. Elaine Sampson wants him to find her husband. In The Way Some People Die Mrs. Lawrence wants him to find her daughter, Galley. The Drowning Pool is the one exception to this rule, with Maude Slocum asking Archer to investigate a poison-pen letter she’d received, but this is just something to get the ball rolling. The main action of the novel surrounds Archer’s attempt to find the missing Patrick Ryan, just as in this book the search for Galley is passed off to being a search for Joe Tarantine. In short: finding missing people is what Archer does.

Third: the women who hire Archer are all “of a certain age,” meaning perhaps middle-aged though often still possessing a sexual charge. They each, however, also have kittenish daughters who like to sleep around: Una Sand in “Find the Woman,” Miranda Sampson in The Moving Target, Cathy Slocum in The Drowning Pool, and Galley Lawrence/Tarantine in The Way Some People Die. That Galley is the friskiest kitten yet, bordering on being a “crazy for men” nymphomaniac, shows that there was something about sexually liberated young women that fascinated Macdonald. And also worth noting is the conflict in every case between these women and their mothers, something Macdonald often linked to classical myth and Freudian psychology.

Galley is different from earlier kittens in that she’s a bad ‘un. It’s not just that “frank sexuality is her forte.” She’s bad. Bad and dangerous: “a single gun in the hands of a woman like Galley was the most dangerous weapon. Only the female sex was human in her eyes, and she was its only really important member.” Put a gun in this babe’s hand and she gets ugly, and “an ugly woman with a gun is a terrible thing.”

In case you were wondering, her full name is Galatea. And what was her mother’s name, you ask? Why she’s Mrs. Samuel Lawrence. Or just Mrs. Lawrence, for short. Back in the day, married women didn’t have first names. Mrs. Samuel Lawrence is even how she introduces herself to Archer, and this despite the fact that her husband Samuel is dead! I still sometimes see letters being addressed to a Mrs. Man’s Name, but only ones that have been written by people who are now in their 70s. In any event, Mrs. Lawrence ends up a lot like James Slocum, withdrawing into her own preferred alternate reality, though, surprisingly, it’s not one that is antagonistic to Archer. She’s just not as fiery a character. I guess Galley got all of her spunk from her dad.

I felt a real tension in this book between Macdonald’s penchant for complexity with his desire to tie everything up neatly in the manner of a well-made plot. Which just means that the narrative of what “actually happened” here is very hard to follow. I’m not sure I managed to keep it straight, though I don’t think it matters much in the end. You’re in it for the atmosphere, that landscape of unreality and dream/nightmare that Archer operates in. One where everyone is guilty of something and blood seems to follow him everywhere (the yolk of an egg “leaked out onto the plate like a miniature pool of yellow blood,” and a bottle with a candle stuck in it at a restaurant is “thickly crusted with the meltings of other candles, like clotted blood”). There are few heroes in an Archer novel. This makes his morality cut and dried. Or is it even morality? Here he is trying to explain to Mrs. Sampson: “She lived in a world where people did this or that because they were good or evil. In my world people acted because they had to.” But then “Perhaps our worlds were the same after all, depending on how you looked at them. The things you had to do in my world made you good or evil in hers.”

My takeaway from this is that good and evil don’t exist in Archer’s world, at least in a form where we can judge people by their actions. There’s no free will. But that’s not an assumption he seems to operate under. It’s more like a crutch or rationalization he’s come up with, something to help him sleep at night. True, when people get in a jam their options start to be reduced, until they’re finally just trapped by a naturalistic drawing of fate. But at some point they chose a path, and their fate is no longer random.

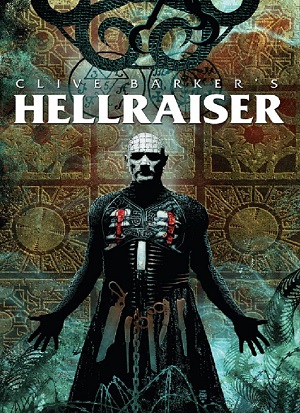

Not just Clive Barker’s Hellraiser, meaning his intellectual property, but a comic actually written by Clive Barker (and Christopher Monfette). Which I can’t say pays off very much as I didn’t care for the writing. There’s a lot of heavy breathing from the Cenobites that’s all just mumbo-jumbo. If you go back and watch the first movie, Pinhead doesn’t actually talk much. Just a handful of lines. In Pursuit of the Flesh he’s making speeches like this: “It is fruitless to wonder how this came to pass . . . History has no place in hell. We live our deaths within a final, unending chapter. Unraveling, unfolding, forever. And there is no prologue for us but pain.” There’s a lot of this stuff, and while it may sound cool, it means exactly nothing.

Not just Clive Barker’s Hellraiser, meaning his intellectual property, but a comic actually written by Clive Barker (and Christopher Monfette). Which I can’t say pays off very much as I didn’t care for the writing. There’s a lot of heavy breathing from the Cenobites that’s all just mumbo-jumbo. If you go back and watch the first movie, Pinhead doesn’t actually talk much. Just a handful of lines. In Pursuit of the Flesh he’s making speeches like this: “It is fruitless to wonder how this came to pass . . . History has no place in hell. We live our deaths within a final, unending chapter. Unraveling, unfolding, forever. And there is no prologue for us but pain.” There’s a lot of this stuff, and while it may sound cool, it means exactly nothing.

As far as I could understand it, the flesh being pursued here was that of poor Kirsty Cotton. Why? I think it has something to do with Pinhead wanting to become human again and he needs to provide her as some kind of blood sacrifice to the demonic powers that be. But I don’t know. And the reason I don’t know is that this book only contains the first four comics in a series and it’s not a complete story arc. It breaks off with a cliffhanger. So I’m not sure what was really going on.

If you want gore, you got it. Those chains with the hooks at the end get a lot of play. Many bodies are torn apart, and the art renders it all quite well. It’s a good looking comic. The story, however, was hard to follow. Something about a team of hell-hunters who each have experience dealing with the Cenobites trying to turn the tables and shut them down. Kirsty seems to be their leader. But it all’s kind of hazy and I didn’t grasp the mythology. The Clockwork Cenobite was a neat addition though.

Not sure I’ll keep going with this series. I’m curious, but not eager. And I watched all the movies!