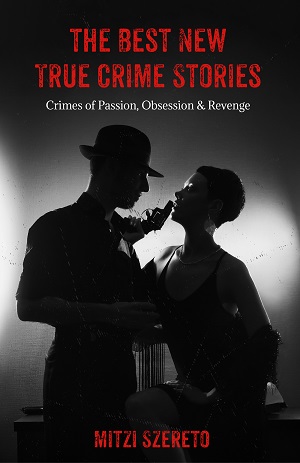

The Best New True Crime Stories: Crimes of Passion, Obsession & Revenge

Ed. by Mitzi Szereto

The crimes:

“I’ve Seen the Dead Come Alive” by Joe Turner: a moody teenager crosses the country to meet a girl he met online who shared his interest in “horrorcore rap.” She is less impressed with him in person and he kills her, her parents, and her best friend.

“Petit Treason” by Edward Butts: in Ontario in the 1870s a woman kills her abusive husband. Despite being an at least somewhat sympathetic case she is sentenced to hang.

“The Crime Passionnel of Henriette Caillaux: The Murder that Rocked Belle Époque Paris” by Dean Jobb: a Parisian society lady shoots and kills the editor of a newspaper, under the assumption that he was going to publish some of her personal correspondence.

“A Young Man in Trouble” by Priscilla Scott Rhoades: the driver of a Brinks armoured car decides to take off with a shipment of “bad money” (old bills slated for destruction).

“The Madison Square Garden Muder: The First ‘Trial of the Century’” by Tom Larsen: Harry Thaw shoots the starchitect Stanford White dead for having corrupted his wife.

“Facebookmoord” by Mitzi Szereto: a social media dust-up between a pair of teenage girls in the Netherlands turns fatal.

“Death by Chocolate” by C L Raven: in Victorian England a woman goes on a rampage poisoning chocolates.

“The Gun Alley Murder” by Anthony Ferguson: a disreputable bar owner in 1920s Melbourne is executed for the murder of a 12-year-old girl. Witnesses against him seem to have been mainly motivated by the offer of a reward for their testimony, and in 2008 a posthumous pardon was issued.

“The Beauty Queen and the Hit Men” by Craig Pittman: a woman has her husband killed as part of the fallout from a messy divorce.

“Because I Loved Him” by Iris Reinbacher: the Sada Abe case. A Japanese geisha/prostitute kills her married lover and cuts off his penis, which she takes with her as a keepsake.

“A Crime Forgiven: The Strange Case of Yvonne Chevallier” by Mark Fryers: a French woman shoots and kills her husband, an eminent politician, when their marriage hits the rocks.

“Bad Country People” by Chris Edwards: a bitter divorced woman enlists the aid of her family in killing her ex and his new wife.

“The Life and Demise of England’s Universal Provider” by Jason Half: the founder of a successful chain of department stores is killed by a man who claims to be his son.

“Revenge of the Nagpur Women” by Shashi Kadapa: at a court appearance, a brutal Indian crime boss is torn to pieces by a mob.

“A Tale of Self-Control and a Hammer” by Stephen Wade: a British man kills his wife with a hammer, perhaps out of jealousy but more likely because he wanted to free himself to start over with his lover.

I quite liked a couple of the other true crime anthologies I’ve read that were edited by Mitzi Szereto (Women Who Murder and Small Towns), but I felt this one came up short.

Just the title suggests a lack of focus. Crimes of passion, obsession, and revenge? That covers a lot of ground, as most crimes are either crimes of passion or committed for personal gain. And even then “personal gain” could be someone’s obsession. (A third category, mental illness or insanity, might fall into or overlap with crimes of passion too.) Then take into account that some of the cases here – like the Brinks guard driving off with bags of cash – still seem to fall outside the book’s broad remit and you basically have a true crime potpourri.

There’s nothing wrong with that, and the stable of writers that Szereto works with are capable enough, but it makes it hard to see the book as a whole as illustrating any one particular theme, even as broad as the triple-barrelled passion, obsession, and revenge. As with her other collections there’s a refreshing geographical diversity (a story each from Japan, India, Australia, and Canada, with two from France), and a number of historical cases as well. Among the latter are some celebrated crimes that I think most true-crime buffs will be familiar with, like Harry Thaw’s murder of Stanford White (the first “crime of the century”), the Caillaux affair, and Sada Abe’s mutilation of her dead lover. I didn’t think they were necessary to go over again here. Then there are a number of more contemporary stories, a couple of which – “The Beauty Queen and the Hit Men” and “Bad Country People” – that I found too involved and confusing to follow in this format. I like short true crime stories, but if the cast of characters is too big then as a reader you can quickly get lost.

There are few general observations that are new. One story, “Death by Chocolate,” even begins with the evergreen adage “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” (A quick digression. The origin of that phrase is a play by William Congreve, The Mourning Bride (1697). The actual lines read: “Heav’n has no Rage, like Love to Hatred turn’d,/ Nor Hell a Fury, like a Woman scorn’d.”) The point being one that most people understand and probably even have some experience of. People fall in and out of love. Nobody likes being ditched. When this plays out in cases of murder we most often see men disposing of wives so that they can move on and women taking revenge on husbands who are looking elsewhere. And while poison has been the method of choice for most women in such circumstances (“the perfect way to escape an abusive marriage . . . cheaper than divorce and easier to get away with than bludgeoning an abuser”), in modern times we see guns being used just as often.

There wasn’t much I made notes on. One item that stuck out was in the Australian case of “The Gun Alley Murder.” This was an infamous miscarriage of justice that was apparently at least partially motivated by the large reward offered. As economists tell us, humans respond to incentives. In this case a number of “witnesses” (dubbed “the disreputables” by defence counsel) provided testimony that seemed made up, either for the reward or because of a grudge they had with the defendant. This made me wonder how often rewards actually work. I think most people, if they have information relevant to the solving of a crime, bring it forward freely. In some cases the reward is meant to overcome the stigma, or risk, involved in being a snitch, though I don’t know how often that’s what’s being weighed.

What else does offering a reward do? I suppose it gets attention, but that’s it. This puts rewards in much the same boat as awards in the arts. Those are meaningless and rarely go to the best work, which would be produced anyway. So they’re basically just a form of advertising. Rewards for tips leading to an arrest may work in the same way.

I was curious as to what percentage of these rewards make a difference so did a bit of looking online. According to one report, “A review by the Los Angeles News Group involved a total of 372 rewards offered by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and Los Angeles City Council from January 2008 to April 2013 to solve violent crimes. Only 15 of these rewards were actually paid out to people who provided information that led to convictions.” That doesn’t seem very productive, though I guess you haven’t lost anything if the money doesn’t get paid out. I also found a 2019 NPR story focusing on the Crime Stoppers organization where the people interviewed called rewards “not wildly productive,” even though it’s impossible “to determine how much of a factor Crime Stoppers’ rewards play since tips and payouts are anonymous.”

It seems like we should have a better idea how well rewards work, given that, as the Gun Alley case shows, such incentives can also be abused and lead to perverse outcomes.

Noted in passing:

The sexualisation of young women is not a phenomenon of the Internet age. Evelyn Nesbit was posing for artists and photographers, sometimes in the nude, before making it as a cover girl for major magazines when she was only 16 (“or maybe younger,” as Tom Larsen puts it). Lana Turner was famously discovered when she was playing hooky from high school at the age of 15 (which I believe she later “corrected” to 16, for legal reasons). A casting director was captivated by her physique (read: her bust) and she appeared in her first film the next year in a brief role that earned her the nickname of “Sweater Girl.”

In the 1870s social hierarchies were very much still part of the law:

At that time, the murder of a husband by his wife was still known by the old English common law term “petit treason” (which also included the murder of a master by a servant, and the murder of an ecclesiastical superior by a lesser clergyman). Next to high treason against the monarch or the state, it was officially the worst crime a person could commit.

Something of this attitude persists in the greater criminal liability for shooting a police officer than killing a man on the street. We still have our hierarchies when it comes to things like insurance, health care, and the law. Some lives are worth more than others and considered deserving of greater protection.

Takeaways:

Perhaps the French are more sophisticated in their permissiveness toward men taking mistresses, but that hasn’t stopped Frenchmen paying a price for such behaviour.

OK maybe Mothers Instinct isn’t so unlikely 🤣🤣

LikeLike

Well, it was based on a French story!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pesky Frenchies!

LikeLike

They’re naughtier than the Scots!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure about that!

LikeLike

I could use a brinks truck full of cash, old or otherwise. Get this condo paid off pronto!

LikeLike

Just go to the bank with bags of old bills and tell them you’re laying down cash money!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s the thing, our mortgage is through an online mortgage place. So that’s not an option 😦

LikeLike

Humph. You could always trying paying them in doggycoins.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if they accept that? I’ve never looked into it. I plan on never using those fake digital currencies…

LikeLike

Wise move. It’s all just gambling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I concur. It’s a speculation of the worst sort and only those running the game are coming out as winners…

LikeLike

We’re in agreement all around this morning!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d say it’s a miracle, but I suspect it’s more of an “age” thing, hahahahaha 😀

LikeLike