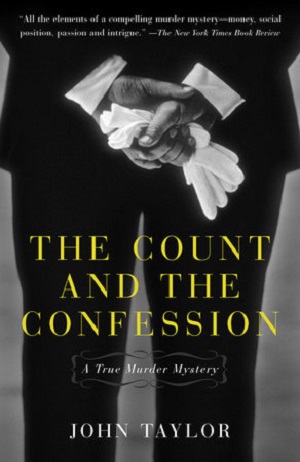

The Count and the Confession

By John Taylor

The crime:

On the morning of March 5, 1992 the body of 60-year-old Roger Zygmunt de la Burde was discovered lying on a couch in the library of his Virginia estate with a revolver next to him and a bullet in his head. Originally considered a suicide, police investigators began to suspect Burde’s lover, Beverly Monroe, of being his killer. Monroe had been with Burde the previous evening and was the last person known to have seen him alive. After a long battery of coercive interrogation Monroe seemed to confess to killing him. Upon being formally charged she denied having been involved and claimed to have been brainwashed by the police. She was convicted at trial, but the decision was reversed on appeal in 2003 and Monroe was released from prison. It’s still unknown who killed Burde, or if it was a case of suicide.

A year or so ago I did a bunch of research into the culture that has grown up online that deals out supposed “hard truths” about dating and relationships grounded in evolutionary psychology and big data. A lot of this on the male side – the manosphere or red-pill community – is openly misogynist, though there are similar hard truths, culled from the same sources, for women to take aim at men with.

I found myself thinking about these findings when reading The Count and the Confession because they provided a helpful paradigm for thinking about the relationship between Roger de la Burde and Beverly Monroe. Helpful in the sense of making understandable what, on the face of it, made little sense to me. This isn’t to say that I took the book as endorsing any of these paradigms, whose validity I find open to question in various ways, but I do think they provide an interesting entry point to the case. With that caveat registered, let’s dig in.

In the first place you have the question of what men want. At the most basic biological level this can be boiled down to reproductive success for young men and end-of-life health care for older ones. Burde wanted both. In terms of reproduction this was mixed in with a twist of Old World chauvinism, as only a male heir would do. He had daughters but they really didn’t count. He wanted someone to carry on his (made-up) family name. This became nothing short of an obsession in his final years, as he took to basically looking for any available womb and inquiring if it might be for rent. And I very much don’t mean he was looking for sex with younger women. He wanted a woman who was capable of having children and that was it. When he found one it was straight off to the fertility clinic and drawing up a legal agreement laying out how all this was going to work (Item 3: “Child/children will carry de la Burde name. This name cannot be changed until maturity or marriage.”).

The last part of the written arrangement, however, also provided for the second biological imperative. Item 6 states that the surrogate “obliges herself to help care and cater to R. B. in his advancing age.” One suspects this is why he kept Monroe around as well. She was past child-bearing age but could still function adequately as a nurse. Oh, those selfish genes!

Then you have the question of what women want. Again staying at the most basic level, this is usually reduced to resources. In cultural terms this translates as status, which is something that even outlives the reproductive imperative. Which is to say, even after menopause women are still mating for status.

But the thing about status is that it isn’t a real thing. The perception of status is the reality. This, at least, is the only explanation I had for Monroe’s attraction to Burde. As far as can be gleaned from the story here, Burde wasn’t just a complete phoney (his claims to being a Polish aristocrat were entirely bogus and even some of his much ballyhooed art collection was apparently forged) but someone who alienated many of the people who knew him best, including his own kids. Despite living in a big house he wasn’t that rich, and money troubles may have been one of the things weighing on him at the end. But he was educated and he did go to swank parties and he dressed well and he lived on that big estate. In short, he had status.

I wasn’t the only one scratching my head over Monroe’s attraction. Even she had to sit down and write out her thoughts on why she stayed with him to try to understand. Meanwhile, the jury found Burde “so despicable a person” that while finding Monroe guilty of murder “it was almost justifiable homicide.” The incredulity of one lawyer at the trial sums the matter up pretty nicely:

Warren Von Schuch, who had not known what Krystyna’s testimony would be [Krystyna was the woman Burde had gotten pregnant just before his death], listened with mounting incredulity to her story. The feminist movement would not be pleased, he decided. Beverly with her master’s degree and Krystyna with her Ph.D. in biochemistry and they’re fighting over Roger de la Burde. Twenty-five years of feminism and this was far as they’d gotten.

Even Monroe’s defence lawyer had to go out of his way to address the point. “You may ask yourself why . . . why did this lady, this nice-looking lady sitting behind me, why did she put up with all this malarkey, this junk? Why didn’t she say, ‘I want out of here,’ ‘Hit the road,’ ‘Forget it fellow’? And the answer is . . . she loved him.”

And I’m sure she did. But this begs the question of what is meant by “love.” Wasn’t what Roger felt for the future mother of his children love? Wasn’t it love he felt for the woman, or women, who would promise to “care and cater” to him in his old age? This is where I find the harsher, evolutionary psychology approach to relationships comes into things. It’s incredible to me that Monroe could have loved someone like Burde, but if you translate “love” as an attraction to a man who had status and presumably some charm, however false, then it makes sense. One of the harsher mantras among the red-pill community is that women don’t fall in love with a man but a lifestyle. The lifestyle is something Burde had. The man was worthless.

I don’t know if that’s what was going on. It’s just a way of viewing the personalities involved through a particular lens. But in a “true murder mystery” like this you naturally start looking around for guideposts. For what it’s worth, it seems highly unlikely to me that Monroe killed Burde. Her behaviour after the fact, especially in relation to the police, doesn’t make any sense if she did. Her “confession,” such as it was, was so obscure as to seem almost surreal even when placed in context. It also appears to have been co-opted, and the behaviour of the police went beyond the usual (and inevitably disastrous) tunnel vision into something altogether darker. One of the investigators hired by the defence made a note on how he thought the agent in charge might even have been insane.

John Taylor provides a very full reckoning of the case. Indeed, I thought there was more here than I cared to have, especially with regard to Monroe’s family (one of her daughters played a key role in her appeals). Though not a particularly long book, it feels heavier than its page count and I could have wished it a hundred pages shorter. It does read well, however, and for anyone interested in the psychology of the false confession, or just looking for a true crime story that has the drama of a well-scripted podcast without playing fast and loose with the facts, it can be heartily recommended.

Noted in passing:

Why are polygraph devices or “lie detectors” (I have to put the scare quotes on such a name) still in use? Just to manufacture evidence in cases where the police have nothing else to go on? I think they must be like diet pills for obese people: a magic bullet that will make the problem go away without having to actually do the hard work of losing weight/investigating a crime. They’ve never been shown to have any significant scientific validity and yet they’re still widely employed by law enforcement.

So why are they still with us? Wikipedia provides one answer:

In 2018, Wired magazine reported that an estimated 2.5 million polygraph tests were given each year in the United States, with the majority administered to paramedics, police officers, firefighters, and state troopers. The average cost to administer the test is more than $700 and is part of a $2 billion industry.

Takeaways:

Innocent or guilty, you have nothing to gain by talking to the police. It won’t do you any good and could get you in a lot trouble.

What about if the police want to talk to you?

LikeLike

Say you want to talk to your lawyer first.

LikeLike

Well, all I know is that Mrs B DOES love me. So if she murders me, it’ll be a complete surprise 😀

LikeLike

It always does . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can’t say I ever mated for status, I’ve been doing it wrong!

LikeLike

On the plus side, you didn’t kill any husbands (that I know of).

LikeLiked by 1 person

No they’re all still alive.

LikeLike